Ancient jawless creatures actively wore down their oral structures.

Before the evolution of the familiar representatives of the animal kingdom, a variety of different structures were tested. Many of these eventually went extinct and have no modern counterparts. This complicates the search for their evolutionary relationships and the interpretation of their physiology and lifestyle.

For instance, ostracoderms are a diverse group of peculiar fish-like creatures that inhabited Paleozoic seas and freshwater environments. They had a massive "armor" at the front that protected most of their bodies. Its "wing" shape allowed the animal to swim using lift and tail movements, despite the absence of paired fins.

Ostracoderms are classified as jawless vertebrates. Unlike agnathans like lancelets, they already possessed a skull but had not yet developed jaws like those of most modern vertebrates. The only exceptions are the living cyclostomes (lampreys and hagfish), which are the meager remnants of the once-diverse jawless group.

It is believed that ancient "armored proto-fish" were the precursors to jawed vertebrates. However, the relationship between osteoderms and cyclostomes is now questioned. Their feeding habits are equally mysterious—it's suggested that they may have fed as filter feeders or consumed detritus (dead organic matter on the bottom).

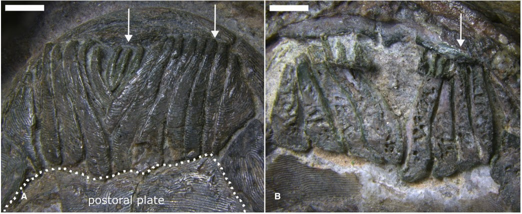

The authors of a new article in the journal Paleontology aimed to understand how the intricate oral apparatus of ostracoderms from the pteraspid group was utilized. They studied the remains of two species—Loricopteraspis dairydinglensis and one of the pteraspids (Pteraspis sp.). Both were found in Lower Devonian rock formations in the UK. The choice of animals was based on the fact that their oral plates were more frequently found and had been studied in detail.

The researchers evaluated the mechanical properties of the pteraspid's oral apparatus, describing its microstructure based on the proportion of bone tissue and using the finite element method. This computational approach characterizes body deformation.

They demonstrated a correlation between the level of mechanical stress (primarily compression) and the proportion of bone tissue. The greater the load experienced by a specific part of the mouth apparatus during the life of the heterostracan, the more ossified it became. The clearest correlation was observed in the area of the characteristic hook of the oral plate. Its backward-facing surface and the very front end were the most cushioned. This indicates that these areas were most actively worn down against other parts of the mouth and food.

The distinctive wear pattern on the bones suggests that the ancient animal actively utilized the rigid appendages of its mouth. Consequently, paleontologists have dismissed the prevailing views of heterostracans as filter feeders. Their oral apparatus was much better suited for scavenging or at least for consuming organic remains on the seafloor.