Rats have been turned into "wine tasters."

Previous studies have shown that pet rats (Rattus norvegicus domestica) can quickly and accurately learn to distinguish between olfactory stimuli. Given this, they were selected as subjects for a new experiment. Specialists from Italy, the UK, and Austria hypothesized that the rats would not only learn to differentiate between two types of wine but also transfer this skill to new samples of the same two varieties during control tests.

The study involved 12 male rats that had previously been trained to recognize the scents of explosives. Before the new series of experiments, the researchers refreshed their skills using simpler scents — strawberry and caramel. They then complicated the task by introducing the rats to the aromas of two types of white wines — made from riesling and sauvignon blanc grapes from different producers and countries of origin. At the end, the researchers assessed how well the rodents adapted to their role as "sommeliers."

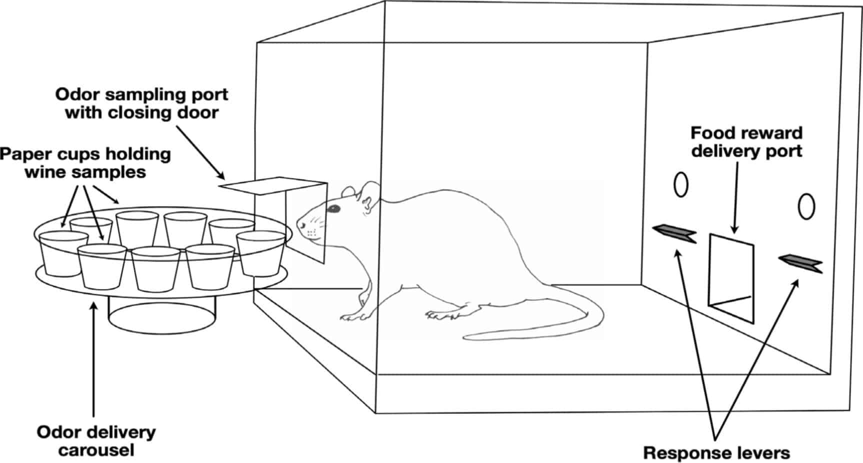

For training the rats and subsequent testing, eight high-tech experimental setups with computerized control were used. Each consisted of a carousel-like system for delivering olfactory stimuli with eight compartments, along with an adjacent box where the animal was located. Sensors, light indicators, and retractable levers in the chamber signaled to the subjects about the necessary actions.

At each stage, the researchers used two types of olfactory stimuli: four rewarded (S+) and four non-rewarded (S-). These were applied to filter paper, placed in paper cups with lids and small holes for scent release, and randomly positioned on the carousel.

As the samples rotated, the eight specimens took turns appearing before the hole in the box, where the rodents inserted their snouts. When a new olfactory stimulus was presented, a light indicator was activated, and when the sensor detected the presence of a rat's nose at the hole, a lever was extended on the opposite side for five seconds. If the scent was rewarding (S+), the rat received a sugar pellet in response to pressing the lever, which then retracted, and the tasks continued. A lack of a correct response (pressing the lever after the S+ stimulus) was counted as a miss.

When the stimulus was from the S- group (non-rewarding), pressing the lever resulted in a pause without receiving a treat. According to the paper, during the wine stage, a lack of pressing further extended the pause. After a break, during which the retracted lever was illuminated, the presentation of stimuli resumed.

During training and testing, the subjects were divided into two groups. Half were assigned one type of odor as rewarding, while the others received the second type. The rats were only allowed to progress to the wine stage after training with the scents of strawberry and caramel when their success rate, meaning presses in response to the S+ stimulus, exceeded 80%. One rat dropped out of the trials at the initial stage.

After multiple sessions, nine rats achieved over 80% success with the samples of sauvignon blanc and riesling. They were given a final test that included not only the familiar wines but also six new samples of the same two types (three S+ and three S- for each).

At this stage, eight out of the nine rats recognized the type of wine for which they had previously received sugar among the new wines, as evidenced by more frequent lever presses. Six subjects distinguished their "own" type of wine with the most confidence. However, accuracy with the new samples was still lower than with the familiar ones: an average of 65% compared to 94%. Individual subjects performed better or worse than the other rats.

An article about this unusual experiment was published in the journal Animal Cognition.