Doctors have targeted human cancer by disguising its cells as pig cells.

The human body has a natural tendency to reject foreign cells. This is why doctors have yet to find an effective way to transplant organs from animals to patients, as opposed to human donors. Experiments involving the transplantation of genetically modified kidneys or pig hearts into living humans have resulted in patient death, despite the new organ functioning well within the body. The first successful case of such a transplant might have been a transplant of a pig kidney to a 62-year-old American in March 2024, but ultimately, death occurred two months after the procedure.

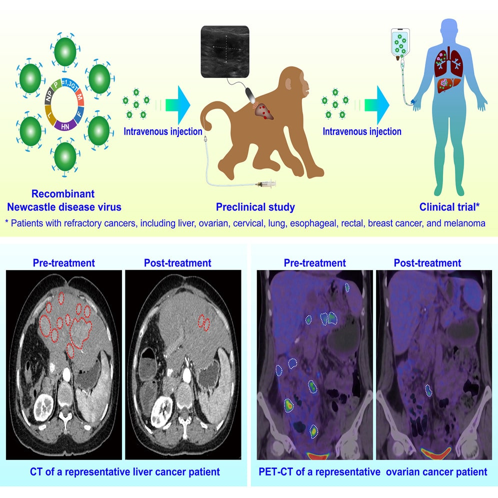

Experts from several universities and hospitals in China have leveraged the human body's capability to reject foreign bodies in the fight against cancer. The results of preclinical and clinical studies of their method were published in the scientific journal Cell.

Doctors employed oncolytic virus therapy: they modified a human-safe Newcastle virus and used it to target malignant tumors. The altered virus introduced sugars onto the surface of cancer cells, which previously triggered a strong immune response and contributed to failures in the transplantation of pig hearts and kidneys. This "masking" prompted the immune system to react to the tumor as if it were a foreign object, leading to its destruction.

Five monkeys with liver cancer that received the virus treatment lived an average of two months longer than their counterparts who were "treated" only with saline solution. For 23 patients with various types of cancer (including liver, esophageal, colorectal, ovarian, lung, breast, skin, and cervical cancers) who were resistant to therapy, the experimental results were less clear-cut.

According to the scientific article, two years after the treatment began, two patients experienced a reduction in tumor size, though it did not completely disappear. In five patients, the tumors stopped growing, but many other participants saw a resurgence in tumor growth after some time. Only two individuals derived no benefit from the treatment.

The authors of the publication noted that the method requires further clinical research. However, they are hopeful that the modified Newcastle virus "could become an anti-tumor agent with significant potential for clinical application in patients with advanced forms of cancer."