Mice provided "first aid" to their unconscious companions.

In emergency situations, people instinctively try to assist an unconscious individual: they check for breathing, perform chest compressions, and revive those who have fainted. Similar reactions in other animals were previously observed only sporadically: for instance, wild chimpanzees touch and lick injured companions, dolphins attempt to push a distressed peer to the surface, and elephants sometimes turn over the bodies of deceased relatives.

However, scientists have long debated whether such actions can be considered conscious help or merely curiosity. Laboratory studies on mice have allowed for the first systematic examination of this phenomenon, excluding the influence of external factors.

A team of American neurobiologists led by Li Zhang from the University of Southern California conducted several experiments. The researchers anesthetized the rodents, simulated death, or kept them awake, and then observed the reactions of their peers. The observations lasted for 13 minutes. In 47% of cases, the mice actively interacted with their unconscious neighbors.

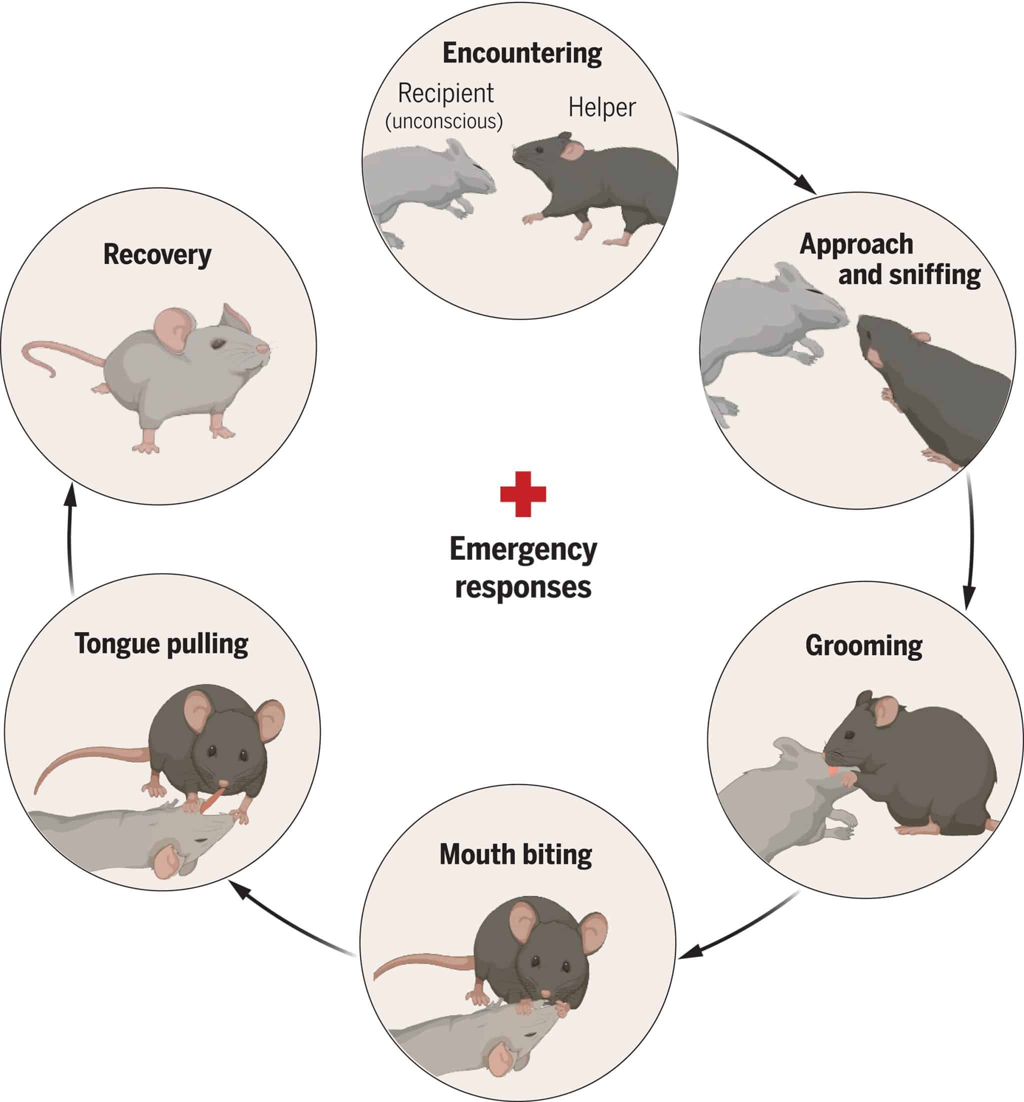

Initially, the mice sniffed the immobile body, then began to lick it. If the partner did not regain consciousness, their actions intensified: the rodents nibbled at the unconscious companion's mouth and tongue, and sometimes even pulled the tongue outwards. This behavior was rarely exhibited if the partner was simply sleeping or if the mice were unfamiliar with each other.

Interestingly, these actions had a practical effect: physical stimulation accelerated the awakening from anesthesia. The mice ceased their "rescue operations" as soon as their companion started to move.

In a separate experiment, the researchers carefully placed a non-toxic plastic ball in the mouth of an unconscious mouse. In 80% of cases, the assisting rodents successfully extracted this object, thereby clearing the airways.

“If we had extended the observation window, the percentage of successful actions by the rodents might have been even higher,” explained Huizhong Tao, a co-author of the study.

The scientists also discovered a neurobiological basis for "first aid" in mice. Neurons that produce the hormone oxytocin (known as the "trust hormone") were activated in the hypothalamus only upon contact with unconscious peers. When these neurons were artificially disabled, the mice stopped helping their partners. Conversely, stimulation of these cells enhanced their activity.

Although Zhang's team is cautious in their conclusions, they believe that such behavior is innate. Assisting helpless peers is likely an ancient evolutionary mechanism that increases the chances of group survival. Oxytocin, present in all mammals, may play a crucial role not only in forming attachments but also in emergency situations. Neurobiologists now plan to investigate whether similar behavior exists in other social species, such as rats or dogs.

For more details on the research findings, refer to the article published in the journal Science.