Some Dyson candidates turned out to be "beacons" from deep space.

In 1960, American physicist Freeman Dyson proposed that advanced extraterrestrial civilizations construct gigantic astroengineering structures around their stars to harness stellar energy. This involved a spherical shell built around the parent star, with a radius comparable to that of planetary orbits. Shortly thereafter, these hypothetical structures were referred to as Dyson spheres.

If such megastructures truly exist in space, they could theoretically be detected by excess infrared radiation emitted from the artificially heated inner surface of the shell. In other words, a sign of a Dyson sphere would be a source of infrared radiation with an atypical spectrum that cannot be easily explained by astrophysical processes, but fits the Dyson sphere models with temperatures ranging from 100 to 700 Kelvin. For over 60 years, astronomers have been searching for such objects by analyzing data on celestial bodies exhibiting anomalous emissions.

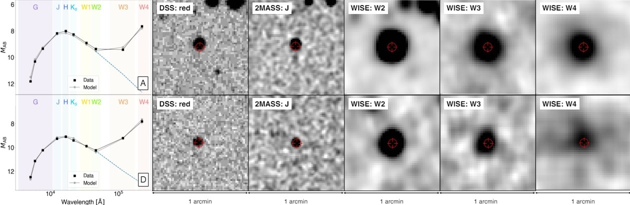

In 2024, two teams of astronomers from Sweden and Italy published a paper detailing their search for candidates for Dyson spheres. The researchers analyzed five million stars in the Milky Way and identified seven candidates showing signs of excess infrared radiation. All seven candidates were located near red dwarfs (spectral class M).

Astrophysicists from the UK, Malta, and participants in the American SETI project decided to investigate what the previously discovered objects really are and whether they can indeed be considered candidates for Dyson spheres. The scientists focused on the brightest candidate—object G.

This object was chosen for two reasons. First, data from the infrared space telescope WISE, which the previous research team utilized, indicated that the suspected sphere emits excess heat in the infrared range. This aligned with Freeman Dyson's theory—the hypothetical shell around a star should absorb its light and re-emit energy as heat.

Second, object G was the brightest in the radio range among all candidates. This was seen as a hint of possible radio technology usage by an extraterrestrial civilization (for example, energy transmission or the disposal of "thermal waste" via radio waves).

To test the hypothesis, astrophysicists employed a ground-based network of seven radio telescopes combined into an interferometer—e-MERLIN (UK). This setup provides high resolution, which helps distinguish compact sources, such as a Dyson sphere, from extended ones like galaxies. They also utilized the European VLBI network—a global array of radio telescopes capable of capturing minute details in radio signals.

Data analysis revealed that the true source of the radio waves (with a temperature of 108 Kelvin) is located far beyond the Milky Way, and its coordinates did not match the position of the candidate object. This means it is situated behind the red dwarf around which researchers suspected the hypothetical Dyson sphere. Signals from the source "overlapped" with observational data, creating the illusion of a technosignature. The scientists reported this in a paper published on the electronic preprint archive arXiv.org.

It turned out that the nature of object G can be explained by a background source of radio emission—an active galactic nucleus (AGN)—a supermassive black hole at the center of a distant galaxy. This black hole absorbs surrounding material and then "spits out" energy in the form of radio waves. AGN are often surrounded by dust clouds that heat up and glow in the infrared range. As a result, a "double" effect occurs: the active galactic nucleus brightly "shines" in both radio and infrared ranges, mimicking the signs of a Dyson sphere.

Further analysis of other Dyson sphere candidates revealed that at least two more of them can also be explained by background sources of radio emissions—active galactic nuclei.

The optical range space telescope Gaia and the infrared orbital observatory WISE, which the astronomers from Sweden and Italy worked with, could not distinguish a nearby star with a hypothetical megastructure from a distant active galactic core. Only ground-based radio telescopes with high resolution, such as e-MERLIN, "saw" the difference.

The researchers found no evidence of Dyson spheres among the three checked candidates but gained new insights in analyzing cosmic data. This represents a step forward, not a dead end—now the search will become even more precise.

Astrophysicists plan to examine the remaining candidates using next-generation radio telescopes like the world's largest radio interferometer SKA (Square Kilometer Array), which is set to be unveiled in the late 2020s. Its sensitivity will be 50 times higher than that of current instruments. If Dyson spheres exist, SKA will be able to quickly distinguish them from cosmic "noise."