Hawking's theory explains the "impossible" black holes of the early universe.

In space, two primary types of black holes are observed. The first type consists of stellar-mass black holes, which are the result of the collapse of the core of a "dead" and very massive star. The second type includes supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

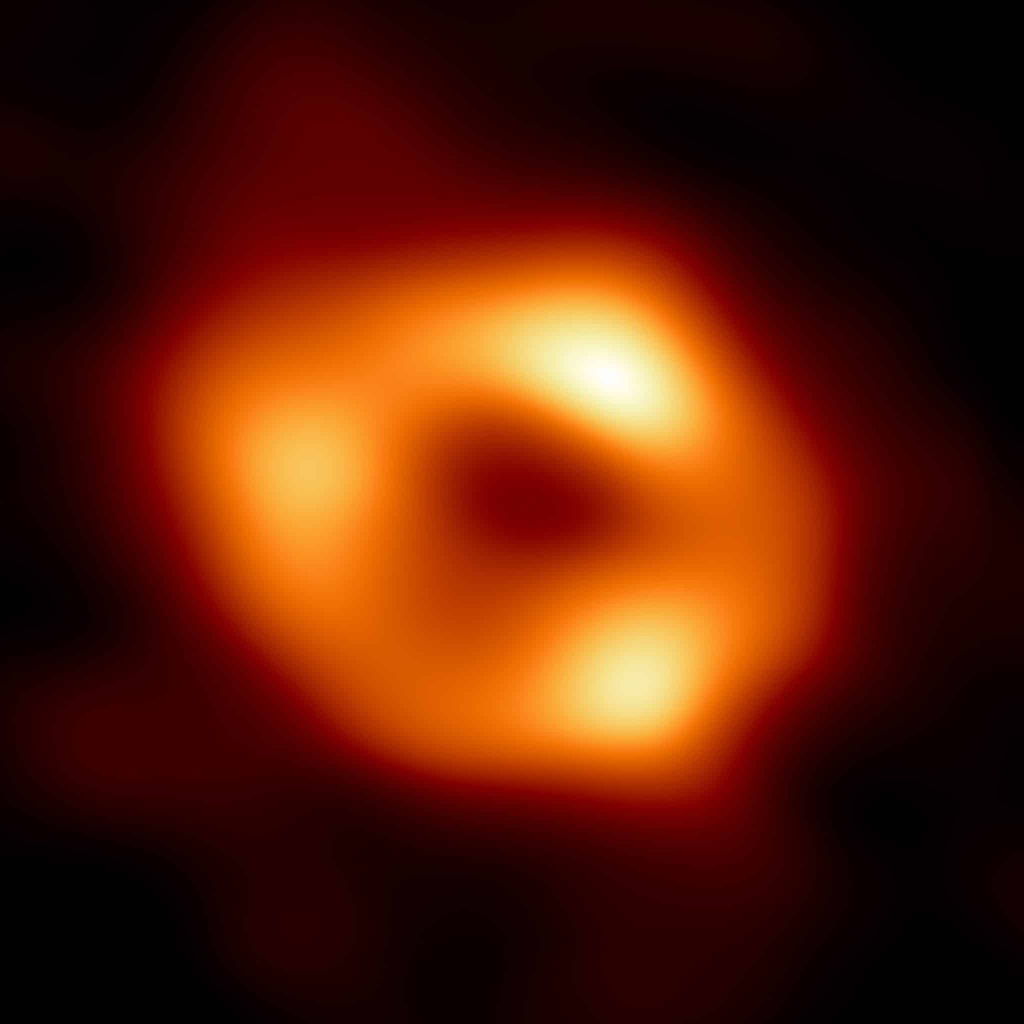

For instance, at the center of the Milky Way, there is a black hole with a mass of four million Suns, while in the M87 galaxy, the central supermassive black hole contains billions of solar masses. This does not surprise astrophysicists: over billions of years, both types of objects have had ample time to accumulate such mass.

Serious questions arose after the James Webb Space Telescope began sending images of the most distant galaxies. These images capture them as they were in the first billion years of the Universe's existence, which is currently estimated to be 13.8 billion years old.

In these young, almost newly formed galaxies, black holes with masses at least in the millions of Suns are observed. This means that in such an early Universe, there were already roughly similar black holes as in the center of our relatively large galaxy, which is about 12 billion years old. We need to understand how this is possible.

This goal has recently been taken up by researchers from Italy. They shared their insights in an article for Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (available on the preprint server arXiv.org).

The scientists noted that until now, two main scenarios for the formation of supermassive black holes have been considered. The first option is that it results from the merging of stellar-mass black holes and the gradual absorption of surrounding matter. As astrophysicists explained, this version does not suit the most distant objects: in the few hundred million years following the Big Bang, this method would not have been able to produce what we observe in the center of the modern Milky Way.

The second scenario suggests that massive amounts of matter in the young Universe collapsed into black holes all at once. However, this also does not appear convincing to scientists: according to them, the conditions for the formation of such "heavy seeds" of supermassive black holes are not entirely clear. Therefore, researchers had to consider another possible alternative: they proposed that the black holes at the centers of galaxies are the result of many hypothetical primordial black holes gathered together.

The idea of such objects was actively advocated by Stephen Hawking. He suspected that relatively small black holes arose all over the Universe shortly after it was filled with the first matter: in the very early Universe, it was still compact, so matter must have been very densely packed, leading to the collapse of its super-dense clumps. Hawking believed that the still-mysterious dark matter consists precisely of these primordial black holes.

Unfortunately, the search for these objects in space has so far been unsuccessful. However, as emphasized by the Italian astrophysicists, if these primordial black holes truly existed, then they could have easily formed what we see in the images from the Webb telescope during the first billion years of the Universe.

There are also alternative explanations for the rapid mass accumulation of black holes in the ancient Universe — models of cyclic cosmology. In these models, the Universe has had numerous black holes since the Big Bang, as they were inherited from previous cycles of the Universe. Naked Science wrote about one of the popular concepts of this kind, the theory of Nikolai Gorky.