Paleontologists have detailed the aftermath of battles between giant armadillos.

Not long ago, the Earth was inhabited by representatives of the Pleistocene megafauna. These were particularly large mammals from various orders—mammoths, saber-toothed tigers, giant sloths, armadillos, and others. However, their numbers soon began to decline, and around 10-12 thousand years ago, most of them completely vanished.

The main reason for the extinction of megafauna is not hard to guess. They disappeared from continents and islands as humans emerged. Hunters were quite eager to secure dozens, if not hundreds, of kilograms of meat in one sitting.

Among the most remarkable giants of the Cenozoic era were glyptodonts and their relatives—the giant armadillos. They belong to the same order as the living armadillos (Cingulata) from the clade Xenarthra, which inhabit the New World. However, the extinct armadillos were significantly larger—up to three meters in length and weighing two tons.

Previously, traces of human tools were found on the remains of these ancient animals, indicating that people inhabited South America 20 thousand years ago. A new article in the Journal of Mammalian Evolution detailed the findings of ancient armadillos interacting with one another. Brazilian paleontologists examined numerous fossils discovered in South America and held in museum collections. These represent 11 genera from different eras and "weight categories." The study utilized a digital microscope and X-ray imaging for the fossils.

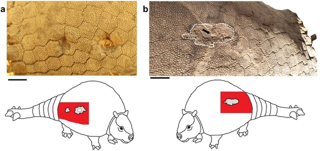

Paleontologists had already hypothesized that armadillos used their massive tails as clubs. Primarily, this was not against predators but during intraspecific confrontations. This includes male battles for females—in this case, they resemble ankylosaurs, which also combined an exoskeletal "armor" with something akin to a mace at the end of their tails. The injuries observed in four of the examined genera (Panochthus, Hoplophorus, Glyptodon, and Propalaehoplophohrus) support this hypothesis.

The nature and location of the injuries correspond to blows that ancient armadillos could inflict upon each other. For some, the injuries consist of missing bone plates on the side, while for others, they fused together as the wounds healed. Occasionally, the shell was punctured through, or a severe festering wound developed, with the infection affecting the bone. Nevertheless, the armadillo survived.

All this vividly indicates the immense striking power of glyptodonts. Their smaller ancient relatives show no signs of combat. Perhaps they did not engage in tournaments or struck each other with insufficient force to leave severe injuries.