Paleontologists have detailed the skeleton of the largest Ramphorhynchus, which has been preserved in a museum for over 150 years.

In 1862, a pterosaur skeleton was added to the collection of the Natural History Museum in London, discovered in the Solnhofen limestone near the town of Eichstätt (Germany). The formation in that region dates back to the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period, indicating that this ancient reptile lived approximately 149.2 ± 0.7 to 143.1 million years ago. This site has frequently yielded Rhamphorhynchus, a genus of tailed pterosaurs, which has allowed paleontologists to model the biomechanics and growth characteristics of these flying reptiles. Additionally, specimens from this location have revealed the diet of pterosaurs—they turned out to be piscivorous and occasionally hunted squids.

The specimen that arrived in London over 150 years ago is unique. It is a three-dimensional (as opposed to other flat specimens) partially restored skeleton that has been well-preserved: it includes the skull, vertebrae, ribs, wing elements, limbs, and more. It is particularly surprising that it was almost unknown to science. It was referred to modestly as "specimen No. 82" and immodestly as "the largest of the known specimens," yet a detailed description of the discovered pterosaur has not been published to this day.

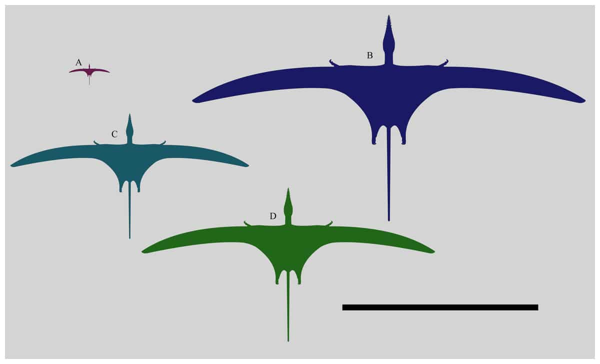

Two paleontologists—British David W. E. Houn and American Sky N. McDavid—studied this skeleton, identified the species it belonged to, and presented their findings in an article for the journal PeerJ. According to the researchers, the pterosaur is "exceptionally large," or rather, record-breaking. Some bones are nearly a third larger than the second-largest Rhamphorhynchus, which is already extraordinarily large. To illustrate, the sizes of the skulls of the first and second are 201 and 150 millimeters, respectively. In simpler terms, this is the largest known Rhamphorhynchus—its wingspan reaches nearly 1.8 meters.

Due to its impressive size, earlier studies categorized it as a new species—Rhamphorhynchus longiceps. However, in a recent article, the authors indicate that the skeletal proportions correspond to the species R. muensteri, which was first described in 1831. The preserved teeth of the flying reptile and the structure of its jaws further supported this conclusion. Additionally, intraspecific variability among these pterosaurs is low. So, what could explain such gigantism?

The smooth structure of the bones and the worn sutures between skeletal elements suggested to paleontologists that they were dealing with a fully grown mature specimen of Rhamphorhynchus. It is worth noting that among the more than a hundred discovered skeletons of these pterosaurs, most were young, meaning they simply hadn’t had enough time to grow significantly. Although the specimen currently appears to be a giant, in the Jurassic sky among other adult representatives, it may not have been particularly large.

The unusual size of the Rhamphorhynchus diversified the presumed diet of these pterosaurs. Young individuals, as they grew, may have transitioned from eating insects to the previously mentioned fish and squids. However, large adult Rhamphorhynchus were quite capable of consuming terrestrial quadrupeds.

If this is the case, then the rarity of such large individuals is understandable—they perished on land, not in lagoons where the environment preserved their skeletons for millions of years. The authors of the article suggest that the large size allowed these pterosaurs to fly deep into the continent and be versatile predators. Among modern analogs, paleontologists compared Rhamphorhynchus to seagulls, which feed both on water and on land.