Bonobos have been suspected of possessing a "mental model" previously thought to be unique to humans.

The theory of mind, the model of the psyche, or the theory of reason, is an individual's understanding of the mental states of others. In simpler terms, it is the ability to "read thoughts": to comprehend what others know, what they do not know, what they think, or what they feel. This ability allows people to lie, empathize, negotiate, and assist one another. For instance, if a person sees a sad friend, they understand that support is needed—this is the theory of mind in action.

For a long time, primatologists debated whether our closest relatives—the great apes—possess this ability. Scientists observed that in the wild, chimpanzees and bonobos behave as if they understand what their peers know or do not know. For example, if one ape sees a snake and another does not, the first one starts to scream to alert the second. This appeared to be a conscious action: "He does not see the danger—I must inform him!"

When researchers studied great apes in laboratories, the results were mixed. The same test subjects sometimes "read" the thoughts of their partners and sometimes did not. Some experts suggested that chimpanzees and bonobos might not truly understand the thoughts of their peers; the apes’ "warning cries" could simply be mimicry of behavior or a response to fear.

American primatologists Luke Townrow and Christopher Krupenye from Johns Hopkins University attempted to definitively address whether bonobos can consciously alter their behavior to remedy their partner's ignorance. To investigate this, the scientists devised a simple yet effective game involving a human and three male bonobos from the Ape Initiative research center (Iowa). The findings of this study are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

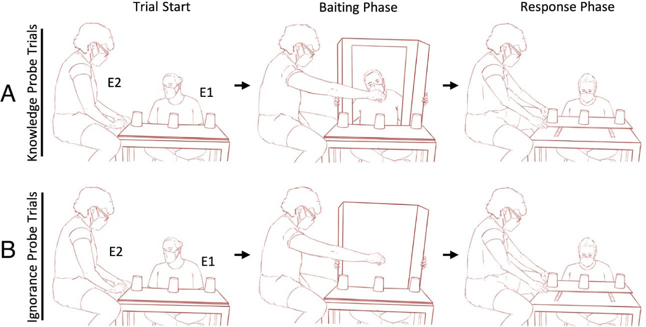

Three inverted plastic cups were placed in front of the ape and the human. The researcher hid a grape under one of the cups, ensuring that the human partner either saw (through a transparent screen) where the treat was placed or did not (an opaque screen was placed in front of the human). After hiding the grape, the barrier was removed. At this point, the bonobos always knew where the treat was located.

If the human knew under which cup the food was, they would give it to the bonobo. According to the researchers, this behavior was expected to motivate the apes to assist. However, when the human did not see which cup held the treat, they waited about five seconds before starting to search for the "correct option," saying, "Hmm, where is the food?" During this time, the researchers recorded how often and how quickly the bonobos indicated the cup with the treat.

The scientists conducted the experiment 24 times for each situation: when the human could see where the grape was hidden and when they could not. It turned out that if the human did not know where the food was, the bonobos pointed to the correct cup faster—on average, 1.5 seconds sooner than the human. They also did this 20 percent more frequently than when the partner observed the process.

The difference of 1.5 seconds may seem small, but it is significant in the context of the experiment. This indicates that bonobos were not merely randomly "poking" at the cups but were consciously choosing the moment to help. Furthermore, the difference in the frequency of hints shows that the bonobos were more actively engaged when they recognized that the human truly needed information.

For the first time in a laboratory setting, primatologists have demonstrated that great apes not only notice their partner's ignorance but also deliberately help to eliminate it. The authors of the study suggested that bonobos possess the rudiments of a theory of mind, previously observed only in humans.

It is worth noting that the animals involved in the experiment were raised among humans, so their communication skills may have developed more than those of their wild counterparts. Townrow and Krupenye plan to investigate whether bonobos use these abilities in their natural environment in the near future.

Krupenye explained that if three great apes demonstrated such a skill in the experiment, it is quite plausible that this ability is ingrained in their biology. This means that the closest common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos, who lived around six to eight million years ago, may have possessed it as well. The ability to "read" thoughts likely facilitated cooperation, information sharing, and collective action. Perhaps this trait provided Homo sapiens with an evolutionary advantage.