Scientists have discovered why weightlessness negatively affects astronauts' vision.

When considering the threats to the human body during spaceflight, radiation is often the first concern. However, its harmful effects in orbit have yet to be observed. Astronauts frequently discuss how their spines elongate in "zero gravity," their muscles weaken, and they experience a decrease in calcium in their bones. On average, individuals lose about 1% of their bone mass for every month spent in space. Some scientists believe that losing 20% or more could lead to survival issues upon returning to Earth.

In recent years, another serious issue has been increasingly highlighted — the deterioration of vision in space. Many became aware of this after the well-publicized case of astronaut John Phillips, whose vision sharpness declined from 1.0 to 0.1 over more than six months of flight. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed flattening of the eyeball. Medical professionals suggested that this occurs in space partly due to increased intracranial pressure. However, at that time, little was known about the specific mechanisms by which microgravity affects the structure of the eye.

Since then, space medical professionals have conducted extensive research, and recently specialists from the University of Montreal (Canada) shared their observations and conclusions. In an article for the journal IEEE Open Journal of Engineering in Medicine and Biology, they reported that they compared the eye structures of 13 astronauts before and after their flights. All participants spent at least six months in space, with 38 percent experiencing their first flight. The average age at the time of the study was 48 years.

It turned out that external pressure on the eye cannot be entirely blamed: the pressure inside the eye itself decreases in space. After the flight, it was found to be, on average, 11 percent lower. It is important to note that post-flight measurements were taken within the first 30 days after landing.

Additionally, there was a significant decrease in eye stiffness — by a whole 33 percent, or one-third of the normal level. The amplitude of the ocular pulse also decreased by a quarter: the central artery of the retina pulsated less vigorously.

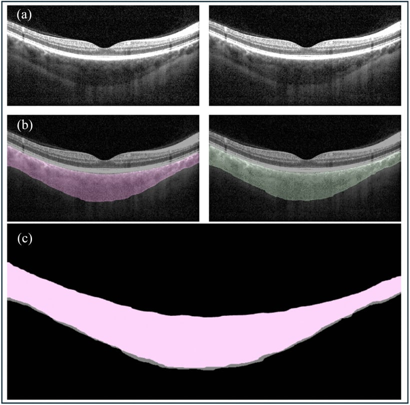

Another interesting finding from the study was a noticeable thickening of the choroid, the vascular layer of the eye that "wraps" around most of the eyeball and nourishes the retina, in some astronauts. Doctors suspect that this is a crucial link in the chain of "space" vision changes: in "zero gravity," more blood flows to the upper body, venous blood accumulates in the eye, and cerebrospinal fluid also approaches it.

It is believed that the increased blood volume in the eye stretches its outer layer, composed of collagen fibers, known as the sclera. As a result, the eye becomes more "pliable" and less resistant to deformation. Interestingly, the vascular layer tends to normalize upon returning to Earth, but the sclera remains altered. Researchers emphasized that these findings are valuable not only for space medicine but for the entire field of ophthalmology as well.

In the 2030s, human flights to Mars are expected, which will take two years or more, including the return journey. Since the gravitational force on the Red Planet is only 38% of Earth's, it may also pose a problematic area for astronauts' vision. How they will cope with this remains unknown.