Astronomers have increased the likelihood of discovering life in the TRAPPIST-1 system.

Red dwarfs, according to astronomers, make up more than 70% of all stars in the Milky Way and the vast majority in the universe overall. These low-mass, dim, and not overly hot celestial bodies have one significant advantage: they have an incredibly long "lifetime," meaning they "burn" nuclear fuel in their cores for extended periods.

This process may even last significantly longer than the existence of the universe itself. In comparison, massive stars like the famous Betelgeuse (with a mass at least 16 times that of the Sun) "burn out" in just 10-15 million years and explode as supernovae.

However, despite their seemingly lethargic and slow nature, red dwarfs occasionally produce flares that make solar flares appear harmless. This has led many scientists to a disheartening conclusion about the impossibility of life on planets around such stars: researchers believe that the radiation from red dwarfs quickly wipes out all living organisms and, for the most part, does not allow conditions suitable for potential life to be maintained—completely evaporating surface water.

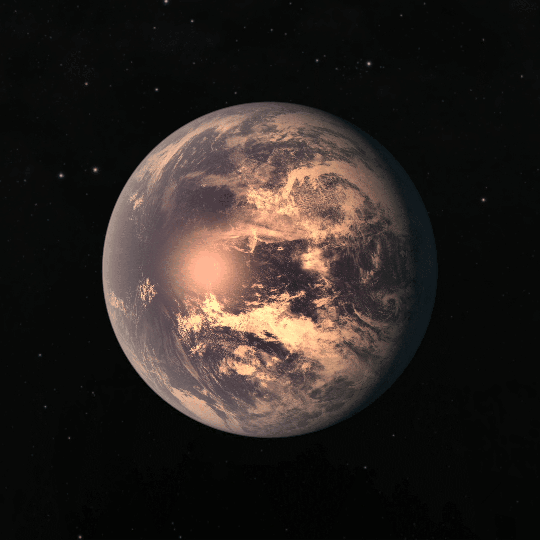

Recently, researchers from the University of Washington (USA) concluded that this is not entirely true. Moreover, in an article for the journal Nature Communications, the scientists noted that it cannot be ruled out that some known rocky planets near red dwarfs may have atmospheres conducive to life. In particular, in the TRAPPIST-1 system, located 40 light-years away from us.

This system is famous for being home to a cluster of roughly similar-sized rocky Earth-like worlds orbiting in nearly circular paths. Notably, three of them are located in the so-called Goldilocks zone—at the perfect distance from the star, where it is neither too hot nor too cold, but just right for the existence of liquid water.

American astronomers decided to compare the situations on two planets in this system: the closest to the star, TRAPPIST-1b, and the fourth farthest, TRAPPIST-1e. Both are many times closer to their sun than Mercury is to ours. However, this sun is a red dwarf, only slightly larger than Jupiter. In this scenario, TRAPPIST-1e falls right within the habitable zone.

Based on all their data about these worlds, the scientists modeled their evolutionary processes. By the way, this system is estimated to be around 7.6 billion years old, which is three billion years older than the Solar System. The modeling indicated that the outlook for TRAPPIST-1b is indeed dire, as observations from the James Webb Telescope suggest. However, the fourth planet has a strong chance of becoming a second Earth.

According to astronomers' calculations, moisture should have rapidly evaporated from the surface of TRAPPIST-1e even in its early stages. But a vast amount of water could have formed in the planet's mantle, later surfacing to create a stable atmosphere.

As the scientists emphasized, it is much easier to study exoplanets that are closer to red dwarfs than those that are farther away, so there are currently no precise observational data on whether TRAPPIST-1e has conditions suitable for life. However, that is precisely what is intriguing. Additionally, promising Earth-like planets have also been observed around other red dwarfs. One of the most well-known examples is the system around Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun.