Astronomers have discovered the conditions under which ancient meteorites were formed.

Extreme conditions in the early Solar System, such as the melting and subsequent accretion of dust particles at temperatures around 1727 °C, led to the formation of chondrules—spherical droplets of solidified molten silicate material. These rounded formations, measuring approximately 0.5-1 millimeter, eventually combined to create asteroids.

The primary building blocks of chondrites are considered to be chondrules—tiny spherical particles that formed from molten material in the protoplanetary disk. Since they contain elements corresponding to the chemical composition of the Sun's photosphere, these ancient meteorites aid scientists in gaining insights into the processes of planet formation. For instance, Naked Science previously reported on a meteorite that broke off from an ancient protoplanet older than Earth.

Astronomers are also intrigued by the peculiar shapes and internal cracks of these celestial bodies. Traditionally, these features were attributed to high-speed collisions with other objects; however, results from a new study published in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters revealed that high-energy collisions are not necessary for the formation of chondrites.

A team of scientists led by Anthony Seret and Guy Libourel from the Côte d'Azur Observatory (France) discovered that the slow "maturation" of chondrites could occur at moderate temperatures under low turbulence conditions, significantly altering current understanding of planet formation.

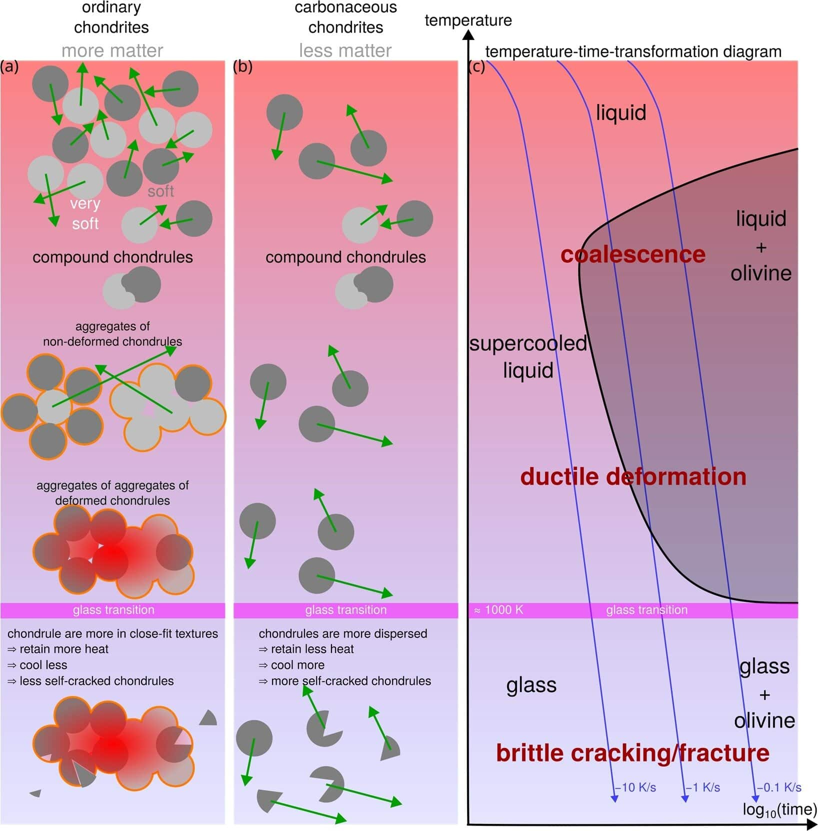

Using computer modeling, the researchers demonstrated that deformation of chondrules and the emergence of cracks were observed at low collision speeds and temperatures around 727 °C. Moreover, cracks (even within a single chondrule) occurred at even lower temperatures, driven by thermal expansion during heating and contraction during cooling between amorphous and crystalline components. External impacts were not required.

The researchers concluded that the first mechanism—plastic deformation at high temperatures—is characteristic of ordinary chondrites (which contain up to 90 percent chondrules), while the second—spontaneous crack formation during cooling—is typical of carbonaceous chondrites (where the proportion of chondrules varies from 20 to 50 percent).

This indicates that ordinary chondrites formed through the merging of many still-plastic chondrules, while carbonaceous chondrites arose at lower temperatures when chondrules became brittle, cracked on their own, and did not have time to fuse. The authors of the study noted that under the conditions they described, not only meteorites but also other rocky objects in the early Solar System could have formed.

The findings provide a new perspective on the formation of chondrites, complementing existing views that are primarily based on chemical analysis. The discovery also supports earlier hypotheses about the formation of ancient celestial bodies in less turbulent conditions.