Physicists have unveiled the properties of "magic mud" used for baseballs.

Baseball is steeped in numerous superstitions, traditions, and rituals, which makes it unsurprising that since the mid-20th century, players in Major League Baseball (MLB) in North America have been rubbing baseballs with a certain type of dirt for better grip. They source this dirt from Jim Bintliff, the sole producer and supplier in the United States. This dirt is often referred to as "magical" or "mystical," and its origin remains unclear, as the location where it was first discovered and is still mined is kept a secret.

It is only known that the dirt was found in a tributary of the Delaware River in New Jersey (USA), along with the proprietary methods used to process it. After collection, the material is strained, excess water is removed, it is washed, and after some manipulations, it is allowed to settle. The dirt used for rubbing baseballs (known as Rubbing Mud) has already proven its effectiveness: MLB has even issued strict guidelines for players on how to use it properly. For instance, the dirt should be applied to the surface for at least 30 seconds on game day, and specific storage rules are outlined as well.

From a scientific perspective, the effects of Rubbing Mud were only tested two years ago, and no significant impact was found; powdered rosin, used in Japanese professional baseball (NPB), performed much better. The authors of a new scientific paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, conducted a more detailed study of the "magical" properties of baseball dirt and revealed several of its unusual qualities.

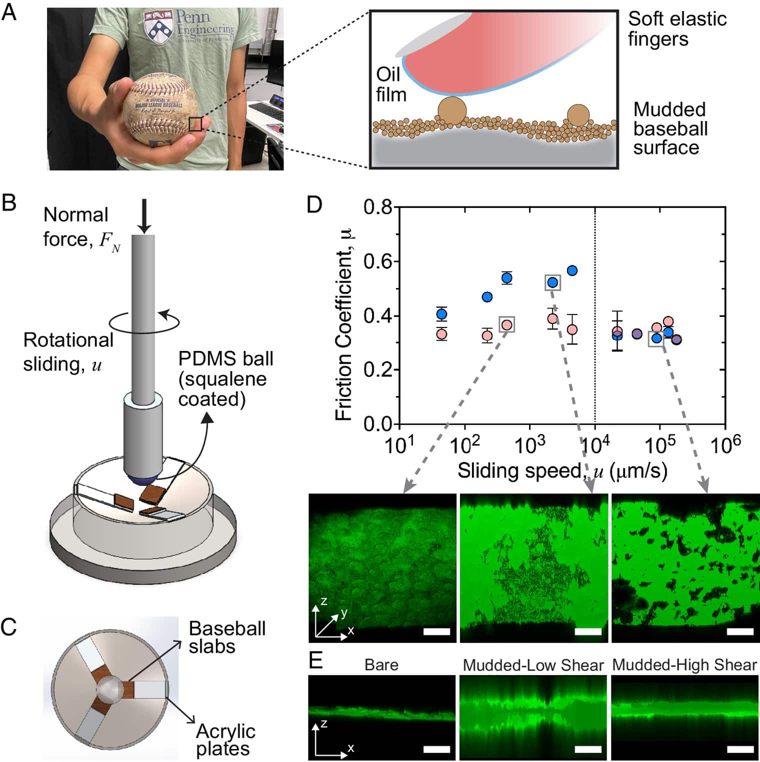

Researchers analyzed the composition of the material and the size of its particles. They examined the microstructure using a laser scanning microscope. The dirt was tested for deformation and flow on a specialized device, and to study the interaction of particles on the surface of the ball with the skin of the pitcher's fingers (the one throwing), physicists constructed a setup and conducted experiments. The lower module consisted of three plates, to which fragments of baseballs—clean, "dirty," and "dirty" but dried overnight—were attached. The upper part of the setup simulated a human finger, replicating its elasticity, and animal fat was used to replace sebum.

The behavior of the baseball dirt reminded researchers of the nature of fine-grained mud and skin creams. In fact, Rubbing Mud can compete with cosmetics in terms of spreadability. The dirt coats the porous surface of the baseball with an even thin layer of particles of various sizes, resembling silt (half clay, half quartz sand), and the water content in the material is adjusted so that it is unstable and behaves like a liquid when friction occurs.

Subsequent experiments showed that angular sand particles, with sizes not exceeding 169 micrometers, double the friction of the ball's surface after drying. According to the authors of the article, if you look at the "dirty" ball on a fine scale, it appears rough, but on a larger scale, it becomes smooth and uniform to the touch.

The researchers addressed the question of whether Rubbing Mud is special, and the answer is both yes and no. They identified its unusual proportions as a distinctive feature, but not the ingredients of the baseball dirt. This material can serve as an effective lubricant if the sand is removed, but it can also function as an excellent friction agent, providing high grip on slippery surfaces. Additionally, the high adhesive properties of baseball dirt (due to the fine particles, adhesion doubled) could be utilized in construction, particularly in binding materials.