Geneticists have traced the Caucasian ancestry of various Eurasian peoples.

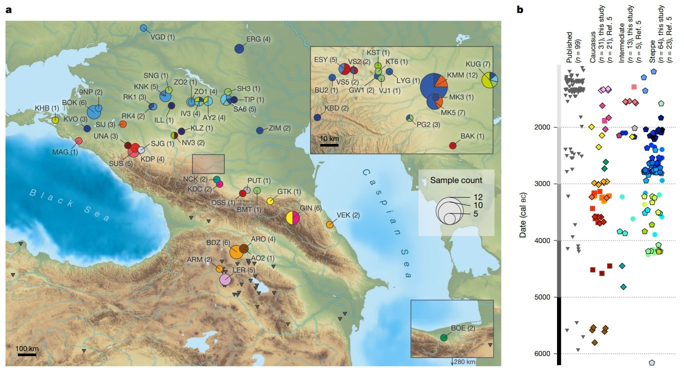

In an article published in the journal Nature, researchers from various countries, including Russia, led by Wolfgang Krause from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Germany), analyzed 131 human genomes from 38 archaeological sites in the Caucasus and surrounding areas, and presented 84 new radiocarbon dates, starting from the Mesolithic — the seventh millennium BC.

The genomes were conditionally divided into two clusters — “Caucasian” and “steppe,” allowing the researchers to determine their origins and trace the genetic lines that gave rise to the pastoral societies of the Black Sea and Caspian regions. This provided rich material for reflection on the rise and decline of steppe culture in the area.

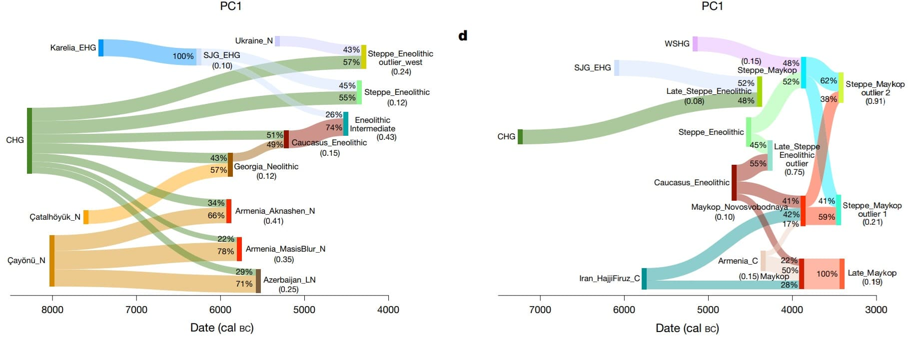

It turned out that even before the Neolithic revolution, the populations of the southern and northern parts of the Caucasus were genetically distinct, which is not surprising given that the Greater Caucasus mountain range serves as a natural barrier to interaction among peoples. In the North Caucasus, hunter-gatherer lineages predominated, with a significant contribution from eastern populations. For instance, the oldest sample from the Satanay cave in the Kuban region, dated to the sixth millennium BC, shares more similarities with samples from Karelia and Samara than with a sample from Ukraine. In the south, there was a noticeable mixing with farmers from the Anatolian Peninsula at that time.

The scientists found no signs of southern genetic heritage in the northern samples, which contradicts the hypothesis of migration from the Fertile Crescent region. However, this hypothesis did not arise in a vacuum, as it stemmed from the similarities in stone industries.

After a millennium, genetic lines characteristic of the first pastoral societies emerged in the foothills of the North Caucasus. They are also associated with the first burial mounds. These show the influence of the southern peoples of the Caucasus and their Anatolian ancestors.

Further north, in the Black Sea and Caspian regions, “steppe” genetic lines began to form, characterized by a more ancient heritage of hunter-gatherers, without contributions from the “southern” populations, but with admixture from the eastern regions of the Black Sea. Since then, contacts between the “Caucasian” and “steppe” clusters have become constant.

The establishment of pastoral societies, including the Yamnaya culture, was linked by researchers to close exchanges between the “Caucasus” and the “steppe.” This gave rise to a unique mobile tradition, the carriers of which invented the cart, dairy farming, and horse breeding.

The flourishing of pastoral societies in the steppe occurred during the Early and Middle Bronze Age. They reigned for two thousand years, which was reflected in genetic stability. Then, around the second millennium BC, there was an active influx of genes from other populations, coinciding with the decline of the steppe cluster. The authors of the scientific paper suggested that ancient herders may have merged into the modern societies of the Caucasus.

Studying the complex interactions between ancient peoples of the Caucasus, the scientists emphasized, helps to better understand the history of the major “players” of the Bronze Age, such as the Maikop, Yamnaya, and Kura-Araxes cultures, which had a profound impact on the formation of populations in Europe and Asia.