Geneticists have discovered an unexpected mass migration to Scandinavia during the Dark Ages.

Around five thousand years ago, the steppe Indo-Europeans began large-scale invasions into Western Europe (and beyond). Representatives of their eastern branch (the Yamna culture) became the ancestors of the Greeks and Armenians, the southwestern branch — of Italic and Celtic tribes, and the northern branch — of Germanic peoples (descendants of the Corded Ware culture). From this point onward, geneticists face significant challenges in tracking subsequent migrations: genetically, all these men shared common ancestors just 5-6 thousand years ago.

It would be beneficial to clarify this period, as the tribes north of Rome and Greece did not possess their own writing system, and what transpired there remains largely a mystery. For instance, around 100 BC, the Teutons and Cimbri nearly destroyed Rome, yet their identity is still debated. Some consider them half-Celts, others view them as Germans (though this is more a conjecture from Julius Caesar than a fact), while some, relying on Pomponius Mela, assert that they migrated from Scandinavia.

A similar narrative exists with the Goths: legends of this people state that around the beginning of our era, they emerged from Scandza (Scandinavia), crossed the Baltic Sea, landed at the mouth of the Vistula River, and gradually migrated via the Dnieper into the Northern Black Sea region, where they established the Kingdom of the Goths. Subsequently, due to a series of tragic events, the Ostrogoths conquered Italy, while the Visigoths invaded Spain, inflicting catastrophic blows to the Roman Empire along the way. However, many historians have debated both the Scandinavian origins of the Goths and later elements of their history for centuries.

Now, researchers from Europe and Japan have developed a method called Twigstats, based on comparing genetic mutations among different people — both contemporaries from various regions and those who lived in different eras — which allows for the establishment of genetic markers for migrations even within very closely related populations, where nearly all are children of just two or three fathers who lived only a few thousand years ago, precisely in the context of Europe post-Indo-European conquest. This method was employed by the authors of a study published in the journal Nature.

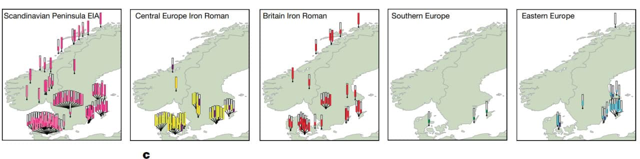

They analyzed the genomes of 1,556 individuals who lived in Europe between 1-1000 AD. In the first 500 years AD, mass migrations occurred from Scandinavia southward: descendants of Scandinavians suddenly appear in what is now southern Germany, Poland, Slovakia, Italy, and southern Britain. These findings align with linguistic data indicating that at that time, Germanic languages had three main groups. The speakers of the first group remained in Scandinavia, the second group became completely extinct, while the third formed the basis of modern German and English. In several instances, Scandinavian migrants were identified by geneticists before they are evident in historical sources. For example, a robust male skeleton from the 2nd to 4th centuries AD was found in York, identified as Scandinavian — although at that moment, there was neither an Anglo-Saxon invasion nor Viking raids. Presumably, he was a slave-gladiator.

Even more surprising were the genetic data from 300-800 AD. For some reason, a reverse movement suddenly began: people from Central Europe, including those of Germanic origin, started to migrate back to Scandinavia, from where their own ancestors had recently departed. Moreover, isotopic analysis of the teeth of several individuals from the Scandinavian region during this era revealed that at least some were born there, although (according to DNA) their ancestors had lived in Germanic lands hundreds of kilometers to the south not long before.

What is unusual is that such individuals comprised several dozen percent of all studied genomes in Denmark and Sweden by 800 AD. For instance, in Denmark, 25 out of 53 analyzed genomes from this period show origins from Central European ancestors. This indicates that the reverse migration from south to north was indeed massive. The reasons for this remain entirely unclear, as Scandinavia at that time was a rather remote, impoverished, and cool part of Europe.

On the other hand, Central and even Southern Europe during 300-800 AD had their own drawbacks. In the 4th century, the Huns emerged in Eastern Europe, striking the state of the Goths, which caused them to migrate westward, subsequently invading the Roman Empire. It is difficult to rule out that some tribes fled from the Huns in different directions — not toward Rome, but northward. In the 6th century, likely due to the migration of steppe rodents caused by the volcanic winter of 536-541 AD, the continent faced an exceptionally severe plague epidemic that wiped out tens of percent of its population. During mass epidemics, peoples can also migrate "wherever the eyes look," seeking regions that they believe have not yet been affected by the epidemics.

Alongside these migrants from Central Europe (primarily into the southern half of Scandinavia), unexpected traces of migration from Britain to northern Norway are also noted. Furthermore, it appears that this was not just a migration of some Anglo-Saxons, who were linguistically and culturally close to Scandinavians: there are evident genes from pre-Anglo-Saxon populations of Britain. And it is unlikely that these were slaves, as significant genetic transmission through the male line in this case is quite improbable. There is even greater exoticism: in southeastern Sweden, primarily on the island of Gotland, archaeologists discovered 14 skeletons whose male-line ancestors originated from the territory of modern Poland and Lithuania (likely from some Baltic tribes).

There are no written records from that era regarding such movements. This is, on one hand, not surprising (the barbarians were illiterate), but on the other hand, it renders the new discoveries made by geneticists exceptionally important and essentially unique information.

For the period after 800 AD, this strange and unrecorded influx of people ceases. Subsequently, geneticists observe what is documented in historical sources: people of Swedish origin appear in the territory of Rus (the Varangians of the "Tale of Bygone Years"), while in England, migrants from Denmark arrive (the Vikings of the Denlow area from Anglo-Saxon chronicles). Interestingly, in Britain, a significant portion of these individuals were found in mass graves, showing signs of violent death. In Rus, there is also an unusual find from the 11th century — the remains of an individual from Britain from the first millennium AD (not a Viking, possibly an Anglo-Saxon).

Migrants from the southern German lands who settled in southern Sweden left almost no genetic traces in the genomes of those Scandinavians found in the territory of Rus. It turns out that the majority of the Varangians in Rus came from central and northern Sweden and Norway.