Uncover the mystery of the wheel's origin! Archaeologists reveal three groundbreaking theories that challenge everything we thought we knew. From ancient Mesopotamia to the Carpathians, d...

Traditional tools like carbon dating have allowed researchers to estimate the approximate time of the wheel's creation and identify several civilizations that could have been its inventors. However, there is still no consensus among scientists regarding key issues such as the exact location, method, and reasons why people needed this complex new technology.

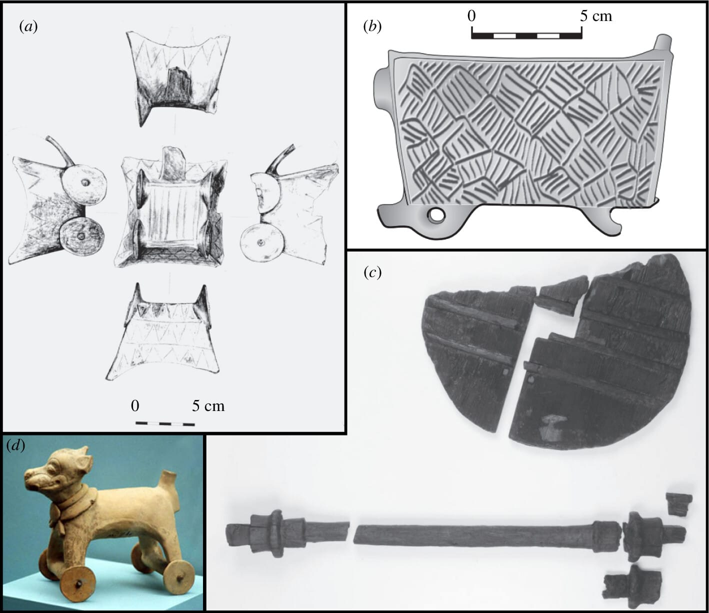

Archaeological evidence of wheels and wheeled vehicles during the Copper Age in Europe, Asia, and North Africa is quite abundant. This includes battle scenes painted on walls, miniature wheels, children's toys, burials in carts, and even early textual references to this technology.

Nevertheless, due to the rapid adoption of the wheel in various regions, it remains unclear where and when it first appeared—or if it had multiple independent inventors.

There are three main theories regarding the origin of the wheel. According to the first, it first emerged in Mesopotamia around 4000 BC and then spread to Europe. Proponents of another theory believe that the wheel was invented on the Black Sea coast, in the area of modern northern Turkey, around 3800 BC.

For a long time, these hypotheses were considered roughly equivalent. However, gradually, archaeologists discovered more wheels in Eastern and Central Europe and even in monuments of the Maikop culture (North Caucasus, Russia).

In the steppe zone, from the Danube in the west to the Manych in the east, more than a hundred burials of the Yamnaya culture were excavated, containing wheels and their clay representations. This led to the suggestion that the wheel was invented by the steppe dwellers, which would greatly simplify their daily lives. However, radiocarbon dating showed that these burials are approximately 5200 years old, meaning they are not the oldest examples.

In 2016, historian Richard Bulliet from Columbia University (USA) proposed a third theory. He suggests that the wheel was invented by miners in the Carpathian Mountains about six thousand years ago, and from there it spread across Europe, the steppes, and into the Middle East.

Bulliet posits that around 4000 BC, the much-desired copper ore became harder to extract. Miners had to dig deeper into mines and carry containers of ore back. Models of late Copper Age carts found in the Carpathian region (in present-day Hungary and Romania) have a rectangular shape with trapezoidal sides—similar to modern mining carts.

To support his theory, Bulliet engaged engineers in the research. Together, they described the evolution of the wheel in the Carpathian region. The findings of their study were published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

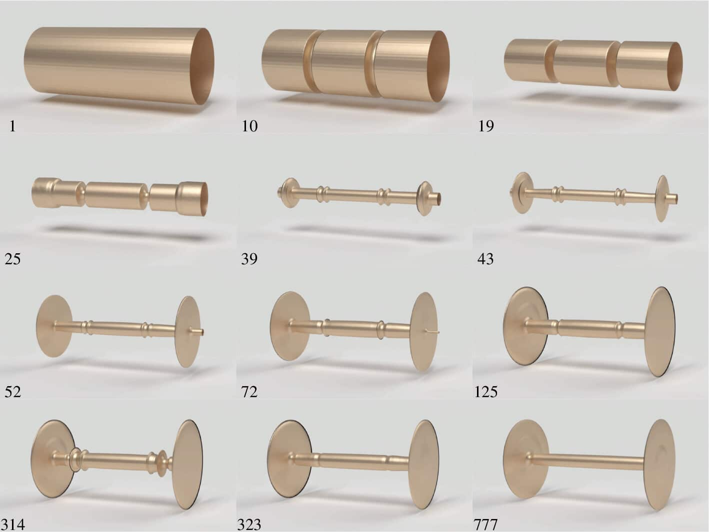

The researchers suggested that three innovations were necessary for the evolution of the wheel. To move a heavy basket or box, people likely used rollers along a path, manually dragging the rollers from the back of the box to the front as they moved.

Archaeologists had previously noted that many rollers had grooves carved near their edges, attributing this to natural mechanical wear. The authors of the new study argue that such grooves represented the first step in transforming primitive rollers into a wheeled system.

According to them, the grooves would allow the box to rest on the rollers and move back and forth without the need to manually drag the passed rollers. On such tracks, people could push a wider cart into the mine—since now they did not need to constantly move alongside it.

The second innovation, according to the researchers, was the wheel pair, or wheels fixed on an axle. They could provide the cart with a higher ground clearance to navigate over stones and other debris in the mine.

The third change emerged about 500 years after the invention of the wheel pair. An innovative inventor created wheels that move independently of the axle. For example, if one wheel lost its point of support, the other could continue moving.

The authors of the scientific paper are convinced that the very conditions of the mines in the Carpathian Mountains forced people to invent the wheel and its modifications. They emphasized that their conclusions do not contradict the idea of independent wheel discovery by other civilizations—though not in Europe.