Methane in Titan's atmosphere is a byproduct of heating complex organic materials.

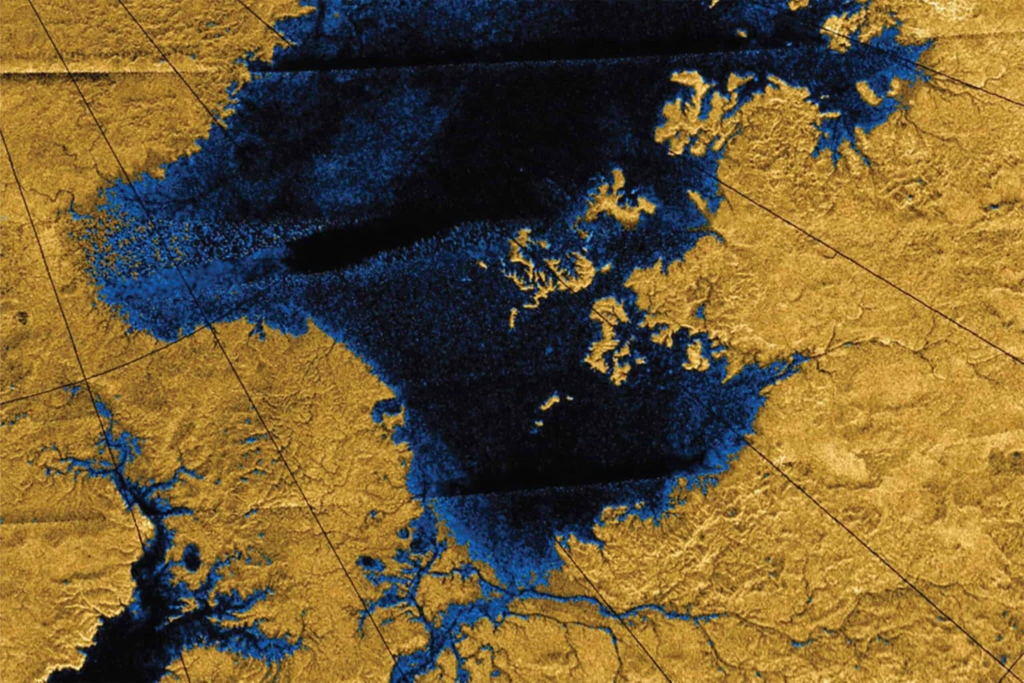

On Titan, the atmospheric pressure is one and a half times higher than that of Earth, while the air density is four times greater than on our planet. Because of this, one could easily glide on wings over the seas of liquid methane, which makes Saturn's largest moon a potential "refueling station" for future explorers of the Solar System: it is a vast reservoir of hydrocarbons.

Planetologists continue to investigate the source of this unusual moon's wealth. One theory suggests that it may have resulted from a massive comet bombardment billions of years ago. Indeed, methane ice or molecules of this substance "embedded" in the crystalline structure of minerals—so-called clathrates—have already been found in over ten different comets. The scenario would seem very convincing if it weren't for one intriguing fact: the presence of gaseous methane in Titan's atmosphere.

Firstly, the surface temperature on Titan is about minus 180 degrees Celsius, which is precisely the freezing point of methane. Secondly, methane that might have entered from space would have rapidly disappeared from the atmosphere of this celestial body due to solar radiation. The fact that it is present there now raises suspicions of some stable source.

Scientists from the United States decided to test whether gaseous methane, along with nitrogen, could be released from Titan's interior. In a recent article (available on the Cornell University preprint server), they described their intriguing experiment: they took samples from the Murchison meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969, and subjected them to conditions thought to exist deep within Titan.

The thing is, this meteorite is very rich not only in carbon but also in complex organic compounds, including amino acids. Its composition has even intrigued seekers of extraterrestrial life and researchers studying the origins of life on Earth. In any case, planetologists believe that this is one of the "building blocks" from which many worlds in the Solar System, including Titan, formed 4.6 billion years ago.

The crushed meteorite material was heated to several hundred degrees and kept under pressures of thousands of atmospheres: this is precisely how it is calculated to occur inside Saturn's moon. It turned out that under these conditions, both methane and molecular nitrogen are successfully released from the samples. Moreover, if the temperature exceeds plus 250 degrees Celsius, the amount of methane produced across Titan would match the quantities observed in its atmosphere. This process also generates a significant amount of nitrogen—approximately half of what is actually present on Titan.

It’s worth mentioning an intriguing theory regarding the origin of some methane lakes on Saturn's moon: planetologists have noted their unusually steep banks and suspected that they might actually be explosive craters filled with liquid: liquid nitrogen in Titan's core heated up, vaporized, creating internal pressure, and eventually burst outward.