The largest known mesozoic creature has been discovered.

Soon after the first vertebrates — the "fish-limbed" like Tiktaalik — emerged on land, some of their descendants chose to return to the seas. This occurred during the Permian period (or even at the end of the Carboniferous), when the mesosaurs began their second "conquest" of the aquatic environment. They had elongated bodies, long tails, and limbs that allowed them to swim effectively and adapt well to marine life.

Mesosaurs swam along the shores of Gondwana, which now corresponds to Africa and South America. Paleontologists increasingly assert that they may have also led a semi-aquatic lifestyle. The morphology of mesosaurs has been well studied, thanks to numerous fossils representing both young and mature individuals of various ages. Based on such studies, they are generally considered to be small, no more than one meter in length.

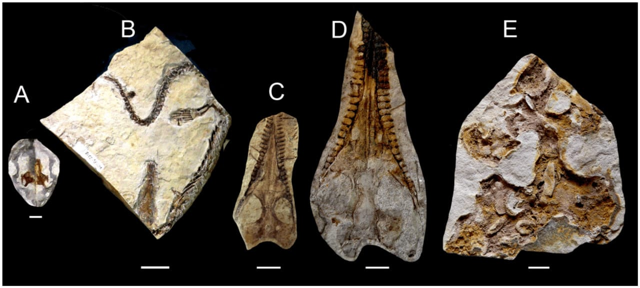

This was challenged by a new article for the journal Fossil Studies. Its authors—a team of paleontologists from Uruguay and France—described a mesoaur fossil that stands out as a true giant among others. It was extracted from the lagerstätten of the Mangrullo formation in northeastern Uruguay. Despite its less than ideal preservation—only two pieces of the skull, the dorsal side of the vertebrae, and some other bones remained—the authors accurately assessed the size of the Uruguayan mesoaur.

Comparing it to another (smaller, yet very well-preserved) Mesosaurus tenuidens showed that the length of the new mesoaur was between one and two meters, with 15-20 centimeters accounted for by the long skull.

This suggests that paleontologists encountered an example of gigantism, meaning extremely large sizes that are much greater than the average in the population. Overall, large mesosaurs, which also indicate their considerable age, are very rarely found. The authors hypothesized that this is due to the preference of "long-lived" individuals for coastal areas, which is not characteristic of the younger and smaller mesosaurs.

As a result, the ontogeny of mesosaurs—their individual development—is now known in great detail. Scientists have samples from all stages of their life cycle, from unborn embryos to giant elders.

The findings align with what is known about the trend toward increased size in the earliest and initially small amniotes. These are primarily terrestrial animals—the ancestors of reptiles, birds, and mammals—that possess specialized embryonic membranes. These membranes protect the animals' eggs from drying out in terrestrial conditions. Surprisingly, some of the very first amniotes were indeed marine mesosaurs—early reptiles or at least representatives of a closely related group of sauropsids.