Some "divine drafts" may have survived the Cambrian explosion.

The paleontological record is typically divided into two sharply distinct parts. The first is the Precambrian, which encompasses a significant portion of Earth's history (about four billion years). The first life appeared at its beginning, primarily represented by microorganisms.

By the end of the Precambrian, during the Ediacaran period, strange large creatures emerged — resembling living fractals with unique types of symmetry and a mysterious way of life. They are referred to as "God's drafts," alluding to the initial unsuccessful attempts of evolution to create animals.

The modern stage of evolution — the Phanerozoic — began with the Cambrian period, which produced many modern types of organisms, many of which are still alive today. However, recently, the boundary between the Precambrian and the Phanerozoic (essentially, the Ediacaran and Cambrian periods) has become increasingly blurred.

On one hand, the offspring of the Cambrian explosion — the rapid emergence of new groups at the beginning of the Phanerozoic — have Proterozoic relatives. For example, Kimberella (Kimberella quadrata) is likely an ancestor of modern mollusks. On the other hand, organisms resembling Ediacaran forms are increasingly being found in later rock layers, at least of Cambrian age. This primarily includes Stromatoveris (Stromatoveris sp.), which resembles feather-like beings with fractal organization similar to Charnia (Charnia masoni).

A new example was discovered by researchers in Estonia, in rocks dating back to the early Cambrian period — the Terreneuvian epoch (539-521 million years ago). Most of this small country is covered by Ordovician and Silurian deposits; however, there is a thin strip of older rocks along the northern coast.

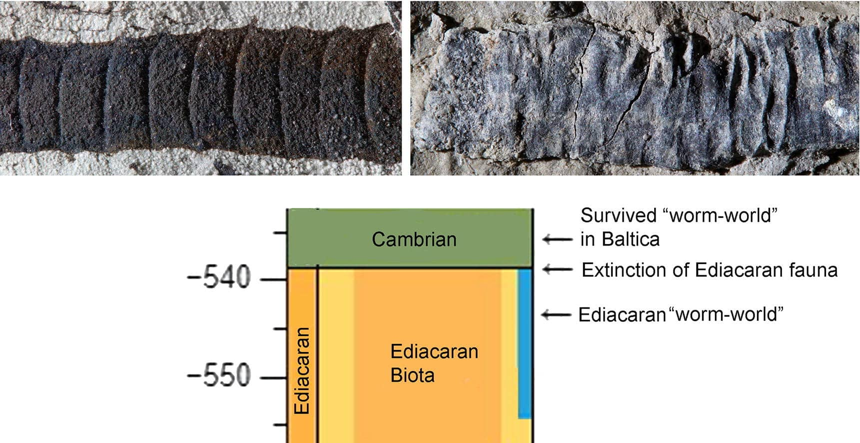

The authors of a new article in the journal Gondwana Research re-examined a museum collection and described 25 specimens attributed to Conotubus hemiannulatus — worm-like creatures with an organic skeleton.

Conotubus was immobile, lived in something resembling a stack of cones closed at the bottom, and likely fed by capturing food with tentacles around its mouth at the top of its body. Nearby, the scientists found skeletons resembling Gaojiashania from the same group of claudinids.

Both of these organisms had previously only been described from deposits at the end of the Ediacaran period — they are representatives of the so-called wormworld, which generally had a more recognizable form than other Ediacaran creatures.

The authors of the study explained this "anachronism" by stating that at the beginning of the Cambrian, the distant and relatively cool Baltic Sea — then a separate continent in the temperate latitudes of the Southern Hemisphere — became a refuge (refugium) where relics of the Precambrian survived. It is also possible that Conotubus hemiannulatus and other claudinids with organic rather than mineral tubes were better adapted to the new environment, thus lasting longer.

In the article, paleontologists urged a closer look at other finds made in modern-day Baltic and its surroundings. It is not excluded that these may also reveal the last of "God's drafts."