Around 10,000 years ago, people relied on steppe cats and foxes for their diet.

The transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and animal husbandry is regarded as one of the most significant events in human history. This process, known as the “Neolithic Revolution”, began in the Southern Levant during the late Epipaleolithic, nearly 15,000 years ago, and continued until the beginning of the Neolithic (which started in the Middle East around 12,000 years ago). This event led to a shift in lifestyle from a nomadic to a sedentary one (in many parts of the world).

During the "Neolithic Revolution," people did not completely abandon hunting; rather, they altered their strategies: they shifted from hunting large game (such as red deer) to smaller animals (like gazelles). Such changes were likely driven by several factors.

Firstly, as the population grew and sedentary settlements increased, frequent hunting could lead to a decline in large animal populations. It became more difficult to hunt these large animals, while smaller animals were more readily available.

Secondly, small game breeds faster and replenishes its populations more quickly, making these animals a reliable food source, especially in a sedentary lifestyle. Hunting small game required less time and effort compared to the lengthy and risky pursuit of large animals.

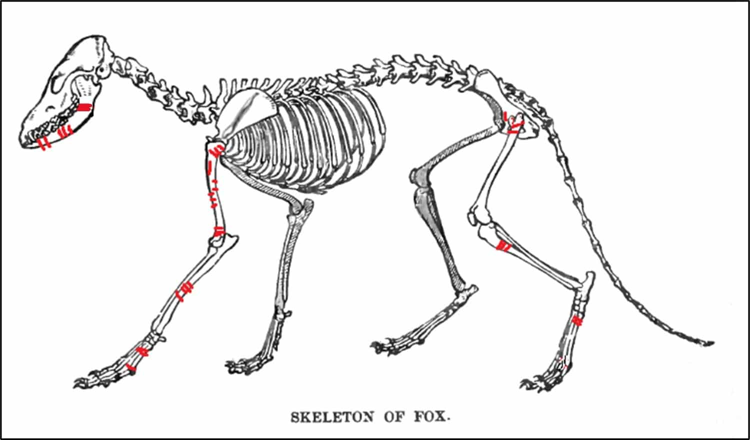

An interesting aspect of these changes involved common foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Remains of these animals have been found in cultural layers of the Southern Levant since the Early Paleolithic, although not very frequently. The number of fossils gradually increased during the Late Paleolithic and peaked in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic between 11,600 and 10,000 years ago. At certain sites, such as the Netiv HaGdud settlement, fox bones are even more commonly found than the remains of gazelles and wild boars, which were considered one of the main sources of meat in the diet of people in the Middle East.

Often at sites in the Southern Levant where fox remains are found, researchers also discover bones of wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica), although in significantly smaller numbers. Many scholars believed that during the Neolithic, these animals might have been used for two purposes: either in rituals (killed for making jewelry from their teeth) or in fur trade, likely hunted for their pelts. As "small game," foxes and wildcats were not considered by researchers, meaning it was long thought that these animals were unlikely to be part of the diet of Neolithic people.

Support for this hypothesis comes from images of foxes found in various parts of the Levant on stone stelae, which likely hold symbolic or ritual significance. For example, such images are found on T-shaped stelae at Göbekli Tepe—one of the oldest temple complexes, estimated to be 12,000 years old.

A team of archaeologists led by Shirad Galmor (Shirad Galmor) from Tel Aviv University in Israel studied the remains of foxes and wildcats at a Neolithic site dating back 10,200 years in the village of Ahihud in Western Galilee and challenged the established views of their colleagues. The researchers concluded that in the early Neolithic period, these animals constituted a significant part of the diet of farmers. This was reported in an article published in the journal Environmental Archaeology.

Galmor and her colleagues found that of all the remains studied, 32 percent belonged to gazelles, 12 percent to foxes, and about four percent to wildcats, Egyptian mongooses (Herpestes ichneumon), stone martens (Martes foina), and European badgers (Meles meles).

The researchers noted markings on the bones of foxes and wildcats that were made with knives. Particularly on the meat-rich limbs, which, according to Galmor, indicates butchering rather than skinning. Additionally, archaeologists often found signs of charring on the animal bones, similar to those found on deer bones—indicating that the meat was subjected to thermal processing: roasted over an open fire or cooked in ash.

Galmor suggested that hunting for foxes and wildcats was carried out with the help of dogs, as traces of dog teeth were found on some remains. Foxes may have become particularly convenient prey, as they likely began to inhabit areas near sedentary settlements, attracted by food waste.

Despite the large number of fox bones discovered by Israeli archaeologists at the site in Ahihud, the authors of the study emphasized that these animals were not a primary food source. A significant portion of meat during the early Neolithic was provided by gazelles. However, regular hunting of small predators became an important supplement to the diet of people who were gradually beginning to raise goats and cultivate wheat and barley.

The findings of Galmor's team will help scholars learn more about the survival methods of people during the transitional period from hunting and gathering to agriculture and animal husbandry.