The organic material on Ceres is native to the dwarf planet rather than being brought in from space.

Ceres is yet another example of the internal structure of a solid-surface world, which, as we explore the Solar System, appears increasingly typical: a rocky core covered by a rather substantial layer of ice. Many scientists believe that beneath this ice, there may even be a salty ocean. The same situation applies, for instance, to Jupiter's moon Europa, Saturn's moon Enceladus, and Uranus's moon Miranda.

It is worth noting that the diameter of Ceres is approximately 950 kilometers, making it three and a half times smaller than the Moon. It is the smallest of all known dwarf planets and simultaneously the largest object in the Main Belt between Mars and Jupiter.

The icy nature of Ceres was first discovered by planetary scientists through the density of the dwarf planet, which is calculated by comparing its size and mass. The density turned out to be just over two grams per cubic centimeter, which is too low for a completely rocky body.

In 2014, observations through the Herschel infrared telescope revealed water vapor above Ceres. A year later, the Dawn spacecraft, which entered orbit around it, discovered a cryovolcano rising four kilometers high on its surface.

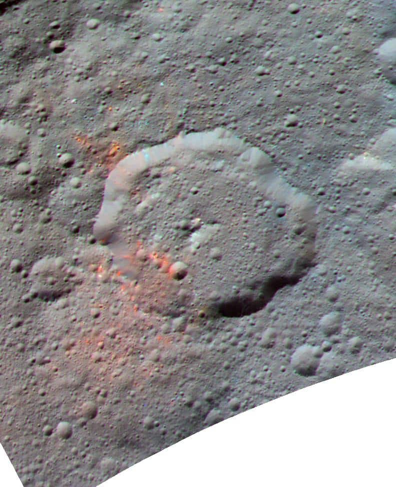

However, the most exciting news was that the spacecraft allowed scientists to detect organic substances in the 53-kilometer Ernutet crater based on the spectrum of light reflected from the surface. The specific types of these substances have not been established, but it has been reported that they are aliphatic compounds. These include, for example, methane, ethylene, acetylene, and fatty acids.

This led to a debate about the origin of the organic material on Ceres. Some researchers were convinced that it was delivered by a fallen asteroid, or more likely, a comet. Others suspected that these were endogenous, meaning native substances of the dwarf planet, which are hidden beneath the surface and exposed as a result of an impact.

Recently, a significant argument in favor of the second theory emerged: data from the aforementioned Dawn spacecraft showed signs of organic molecules in 11 other locations on Ceres. As reported in The Planetary Science Journal by researchers from the USA, Spain, Italy, and Germany, carbon compounds are primarily traced in craters, particularly clearly in the large and deep formations of Yalod and Urvara.

Interestingly, an earlier group of scientists tested in the laboratory how quickly aliphatic compounds should degrade on the surface of Ceres under the influence of cosmic radiation. It turned out that they could last only about a hundred or several hundred thousand years. Meanwhile, the Urvara crater has been established to be hundreds of millions of years old, and Yalod is even older. According to researchers, this suggests that organic material is stored just beneath the surface of Ceres and has been gradually seeping out in impact locations for all these hundreds of millions of years.