A new Jurassic-era cockroach has been discovered, featuring an ancient warning coloration.

The appearance of animals is incredibly diverse and often serves a specific function. The stripes on a zebra's body not only repel flies but, according to some studies, also help avoid predators like hyenas. Some birds — such as nightjars — have plumage that matches the color of tree bark or the landscape, which allows them to blend into their surroundings. In contrast to camouflage, the bright plumage of birds of paradise is due to sexual selection and attracts mating partners.

A well-known example of unusual and functional coloration is the eyespots on the wings of butterflies and other insects. This form of mimicry, which also occurs in reptiles like eyed snakes and other animals, serves to deter predators or redirect their attacks away from vital parts of the victim's body.

A similar purpose is served by warning coloration — aposematism. The bright colors of tropical frogs, the striking patterns on a caterpillar's belly, and similar features are attempts to warn predators that their prey is, if not poisonous, at least bitter and unappetizing.

A new study by British paleontologists from the Open University and the National Museum of Scotland reveals the history of the emergence of warning coloration in cockroaches. The specialists examined a fossil sample from the paleontological collection of the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery (United Kingdom), which was collected 40 years ago. It preserved the wings of ancient insects with distinctive spots. The scientists classified the find as a new taxon and described it in detail in a paper published in the journal Papers in Palaeontology.

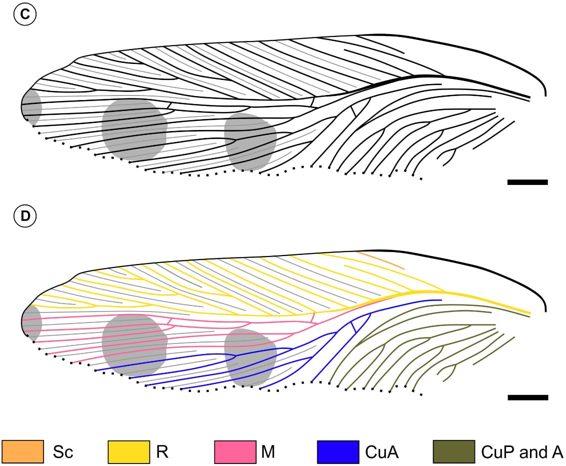

The fossils were discovered in 1984 at the Alderton Hill quarry in Gloucestershire, England. The geological layer dates back to the Toarcian stage of the lower Jurassic period — meaning the insects lived approximately 184.2 ± 0.3 million years ago. The fossilized wings measure up to 13.2 millimeters in length and 3.7 millimeters in width, which is 3.6 times shorter than the length. The hind parts of the wings are missing, but the preserved surface shows 38 veins.

These and other features allowed paleontologists to classify the find as a new genus and species of cockroach — Alderblattina simmsi. The genus name comes from the toponym Alderton Hill, while the species name honors the researcher Michael J. Simms, who excavated the insect 40 years ago.

The main distinguishing feature is three distinct spots (two of which are nearly round), one of which is located at the very tip. The fact that they are spaced evenly apart suggested to paleontologists that the spots were indeed a characteristic of the insect and not a result of diagenesis, the transformation of sedimentary rocks. A similar coloration has been observed in another species of cockroach, Eustegasta buprestoides, whose emerald-green wings are marked on the outside with four orange spots.

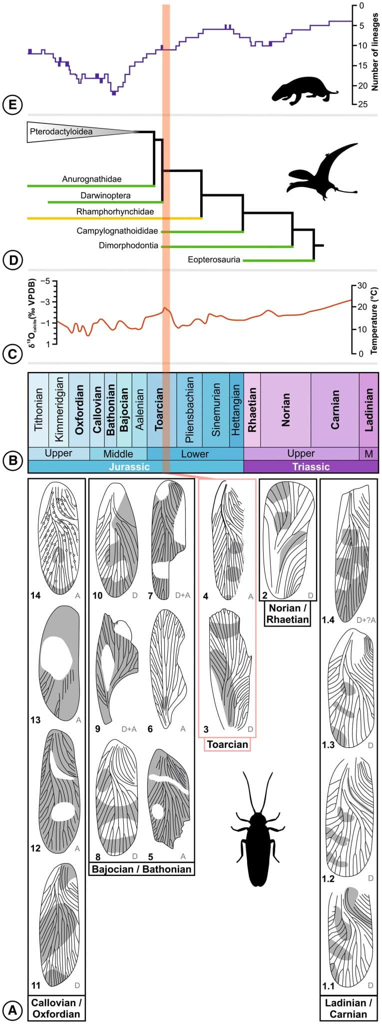

For this species, their function was determined to be a warning to predators. Paleontologists applied the same reasoning to the new species. A. simmsi became the second taxon from the Toarcian stage with warning coloration on its body, and as the researchers noted, the round shape and regularity of the spots indicate the advanced nature of aposematic coloration in cockroaches of that time. Such complex patterns were recorded later, leading scientists to suggest that the described species possesses the most ancient warning coloration known for cockroaches.

This aligns with potential reasons for the emergence of such features. At the turn of the Triassic and Jurassic periods, various insectivorous pterosaurs appeared and mammals began to actively develop, particularly during the Toarcian stage.

Predator pressure may have directed the evolution of insects towards protection — thus, it is likely that the first evidence of warning coloration in cockroaches arose. However, as the authors of the article emphasized, establishing this connection definitively is still challenging.