Russian paleontologists discovered the oldest steppe lizard in Europe in the Tavrida Cave in Crimea.

Among the diverse family of true lizards, or lacertids (Lacertidae), the genus of sand lizards, or steppe lizards (Eremias), is particularly intriguing. They diverged from true lizards several million years ago during the Miocene epoch (23.03-5.333 million years ago) and are believed to have originated from Africa. Sand lizards have spread widely across Asia— as the name suggests, these reptiles prefer steppe and desert regions. However, some species can now also be found in Europe: the colorful lizard (E.arguta) lives in Romania and Moldova, while the swift lizard (E.velox) has been found in the Volga region.

The question of when sand lizards colonized Europe, particularly the Crimean Peninsula, seemed settled. It was assumed that the genus invaded the western territories of Europe no earlier than the Middle Pleistocene, and Crimea during the Holocene, just a few thousand years ago. However, recent findings by Russian paleontologists examining bone remains in the Tavrida Cave in Crimea revealed a fragment of a sand lizard skull that is over one and a half million years old. A comparative description of the find has been published in the journal Historical Biology.

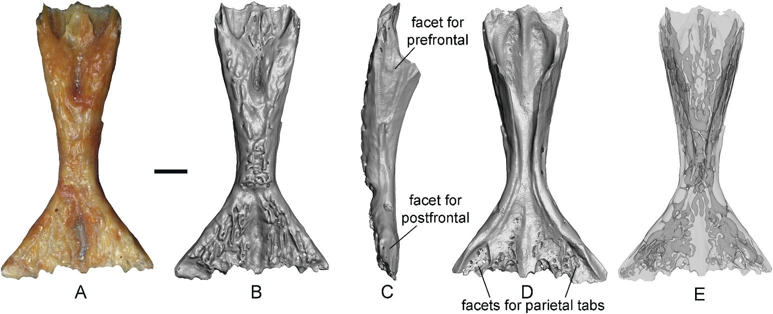

The Tavrida Cave, discovered in 2018, has yielded numerous fossil samples of vertebrates that lived in the early Pleistocene and later, ranging from ostriches and mammoths to bears and saber-toothed cats. Naked Science recently reported how the extinct Iberian lynx (Lynx issiodorensis) from this cave was diagnosed with a fractured front paw with displacement. Now, while washing loose cave sediment in special sieves, paleontologists have found a small frontal bone of a sand lizard shaped like an hourglass.

“The sand lizard certainly did not live in the cave. It likely ended up there, like most other remains of small animals, due to predatory birds, particularly owls, which actively hunted them. Our find is the first from the early Pleistocene and therefore the oldest. Moreover, it is found outside the current range of sand lizards. This suggests that the habitat of these lizards was quite different and, apparently, broader not long ago,” explained one of the study's authors, Elena Syromyatnikova, a senior researcher at the A. A. Borisyak Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, to Naked Science.

The bone was extracted from sediments aged 1.8-1.6 million years, during which the oldest fauna of Crimea lived. Specialists conducted a comparative analysis of the structure of the found bone and noted similarities with the swift and colorful sand lizards, the latter having the widest range of habitats. New data confirms the earliest presence of this genus on the peninsula not in the Holocene (11,720 ± 99 years ago), but in the early Pleistocene—this possibility had been suggested earlier, but convincing evidence had not been found.

“Unfortunately, we could not determine the species affiliation. This is due to the insufficient study of the morphology of sand lizards' skeletons. There is practically no data on the differences in skeletal structure among different species. Moreover, this group has a very sparse paleontological record—fossil finds are extremely rare. It is quite possible that we are dealing with a new species. Only new discoveries can confirm or refute this,” added Elena Syromyatnikova.