Intricate patterns on shells may have contributed to the extinction of certain ammonite species.

The history of our planet is marked by numerous extinctions — from mass events like the Great Dying, which ended the Paleozoic Era, to specific instances of species disappearance, such as the dodo bird and the thylacine.

There are many causes of extinction as well: the age of dinosaurs was interrupted 66 million years ago by what is believed to be a large asteroid that, after colliding with Earth, triggered a prolonged winter. The rapid and massive lava eruptions, now known as the Siberian Traps, are considered the main factor behind the Permian-Triassic extinction.

We should not overlook human impact: due to human actions, the giant flightless moa birds, which had no natural predators, disappeared from the Earth. Hunters with dogs, climate warming at the end of the Pleistocene (2.588–0.0117 million years ago), and increasing diseases all contributed to the complete extinction of mammoths around four thousand years ago.

Extinction can also result from natural development, but tracking such occurrences is challenging. A group of biologists and geologists from China, France, and Germany decided to investigate how the complexity of structure during evolution affected the survival of a taxon. They chose ammonites — a subclass of cephalopod mollusks that are estimated to have gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period or the beginning of the Paleogene, approximately 66 million years ago.

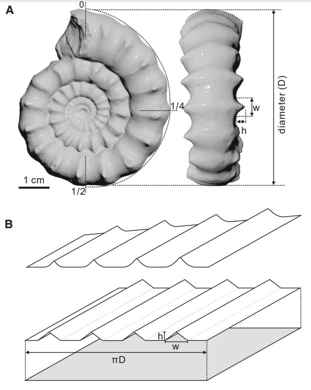

The researchers selected 146 fossil samples for scanning their shells. The new method involved calculating the index of the two-dimensional ornamentation of ammonites — data was taken from photographs of the side and frontal views. They analyzed the number of ornamental details, their density, width, and height.

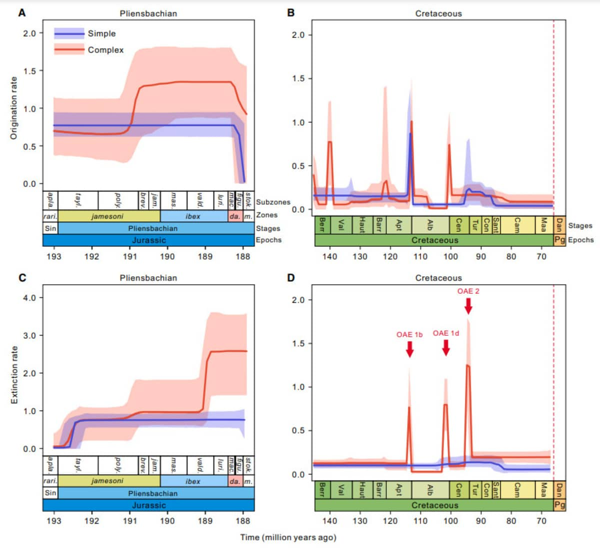

Then, the specialists examined the evolutionary dynamics of mollusks across different time scales to determine whether shell structure complexity influenced it. They selected 211 taxa from the Pliensbachian stage (Early Jurassic period, 190.8-182.7 million years ago) and 462 from the entire Cretaceous period (145-66 million years ago), the longest period. The results of this research were published in the journal Current Biology.

Shells of early Jurassic species, which lived for less than three million years, exhibited more pronounced ornamentation, while those that lived longer were predominantly smooth. Similar conclusions were drawn after analyzing Cretaceous ammonites. Mollusks with vivid ornamentation were short-lived.

The most complex shells were found in the family Liparoceratidae from the Pliensbachian stage. In this family, the researchers traced how several species complicated their structure, leading to a reduction in their lifespan. Only taxa with intricate ornamentation turned out to be short-lived.

“The complexity of shell ornamentation may require greater energy expenditure for its construction, and according to the energetic budget theory, these energy-intensive organisms are unsuitable for living in resource-poor habitats. For example, during the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, significant morphological selection for ornamentation was observed in ammonites, resulting in a preference for species with smooth or weakly ornamented shells, while those with complex ornamentation went extinct,” the authors of the article explained the reasons for the identified correlation.

According to another hypothesis, taxa with more complex structures are much more plastic, meaning their rates of evolution are higher. Such mollusks could adapt by complicating or simplifying their shells depending on conditions such as sea level fluctuations, water temperature changes, and anoxic (low-oxygen) events.

In fact, the peaks in the complexity of ornamentation on ammonite shells clearly correlated with the last phenomena. Nevertheless, the identified pattern shows how a simpler structure of a species enhances its survival.