Researchers tested Aztec death whistles on modern individuals.

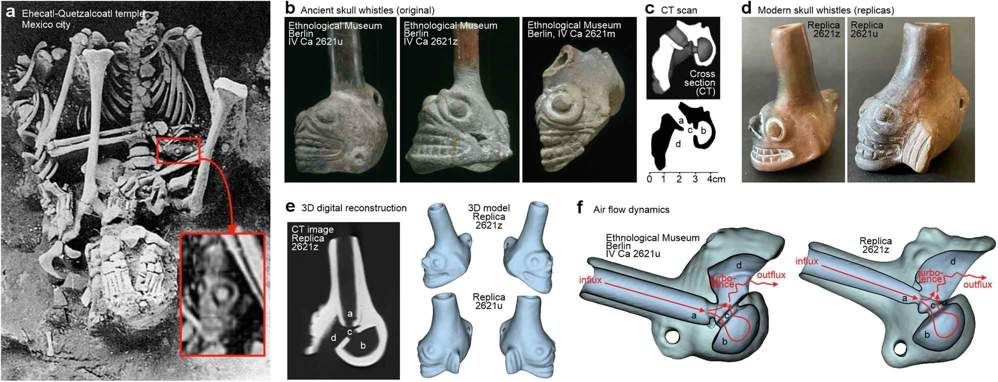

The first object, later referred to as the whistle of death, was discovered by archaeologists in 1999 during excavations at a temple in the ancient city of Tlatelolco (Mexico). In the tomb, the remains of a young man were found, who was likely sacrificed. In the hand of the deceased was a small skull-shaped whistle made of clay.

Since then, various research groups have uncovered many other such items, primarily in Aztec tombs dating from 1250 to 1521. They often formed part of the burial inventory for victims of ritual sacrifices.

The first find was considered a simple ritual ornament, but as more were discovered, it became clear that the holes in these objects were made in a consistent manner—similar to musical instruments. Researchers attempted to produce sounds from them, and it turned out that opinions on the sound of the unusual instrument varied widely among listeners.

For some, the sounds evoked inexplicable fear, while others interpreted it as a warrior's cry, and some only heard the rustle of the wind. Researchers from the University of Zurich (Switzerland) aimed to understand how the human brain reacts to the sounds produced by these unique whistles. An article detailing their findings was published in the journal Communications Psychology.

For the study, volunteers were recruited and asked to listen to the Aztec whistle. The experimenters did not explain what objects produced these sounds, meaning participants were unaware of the specific history and name of the musical instrument.

No one attempted to blow into the authentic ancient whistles of death. There are video and audio recordings made by archaeologists and the initial testers of the whistles. The authors of the new study noted that authentic whistles were always blown with moderate force. However, it remains unclear how forcefully the Aztecs blew into them.

Therefore, in addition to audio recordings of the original whistles, the researchers also created recordings of sounds extracted from well-crafted replicas. These replicas were blown with varying strengths, producing both low and high air pressure in the whistle.

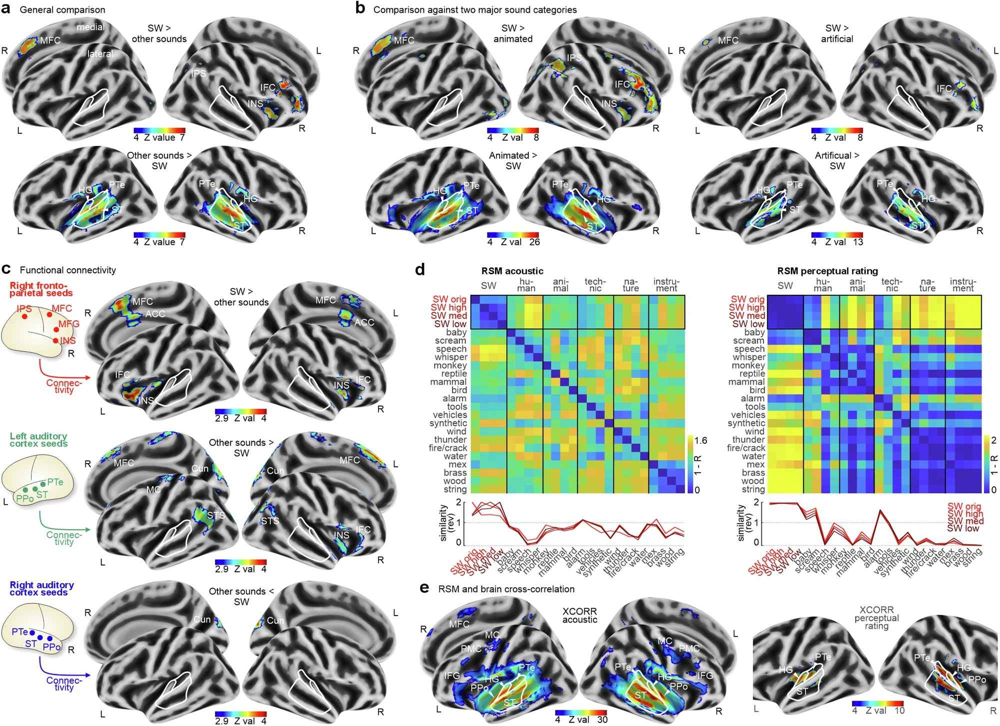

Volunteers were given the opportunity to listen to the produced sounds while their brain activity was monitored. After listening, participants were asked to describe their feelings. It turned out that these unusual instruments produced sounds that listeners perceived as unpleasant and frightening.

The fear experienced by the volunteers was so intense that it caused them to forget about pressing matters and react immediately to perceived danger. Instrumental observations of brain activity aligned with this description.

When the whistle sounded, participants in the experiment exhibited increased activity in the auditory regions of the brain. Simultaneously, monitoring of brain waves showed that the auditory cortex was in a state of heightened readiness, indicating that the brain perceived the sounds of the whistle as threatening.

Researchers believe that the Aztecs understood the frightening nature of the skull-shaped whistles and found ways to use this to their advantage. The question is: how exactly? Previously, after the first experiments with the whistles, some archaeologists suggested that Aztec warriors blew them on the battlefield to intimidate their enemies.

The results of the Swiss researchers' study almost rule out this application: the sounds have a similar effect on all people, instilling fear in both enemies and allies. The authors of the article concluded that, most likely, the whistles were used for ritual and ceremonial purposes, which is why they are most often found in the burials of Aztec victims.

Considering what has been discovered about the impact of the whistles on the human brain, it is possible that they were blown during sacrificial rituals to ward off evil spirits or other dark forces that could attack the deceased during their transition to the other side.