Scientists have reassessed the weight of a giant prehistoric bird known for piercing its prey with its beak.

Birds of prey utilize various hunting techniques, ranging from the stooping dive of a falcon to the impaling of their prey on thorns and spines by shrikes. The family of anhingas (Anhingidae) has developed its own unique method. These feathered hunters catch fish by diving underwater and spearing them with their beaks, much like a harpoon; their specially adapted long necks allow them to pierce their catch instantly. In English, anhingas are referred to as darters, meaning "dart throwers." After hunting, Anhingidae perch on tree branches to dry their feathers.

The earliest fossil species from this family, Anhinga walterbolesi, lived 25-26 million years ago during the Oligocene epoch. To this day, only four species of anhingas have survived, which are also known as snake birds. They inhabit regions in Australia, Africa, Southeast Asia, and North and South America.

Extinct species were much more widespread and reached their peak diversity during the Miocene (23.03–5.333 million years ago). The largest representatives were found in South America, with the largest species recognized as Macranhinga ranzii: according to some estimates, it could weigh up to 18 kilograms. For comparison, the maximum weight of a black vulture is 14 kilograms, and it is essential for birds to conserve weight for survival.

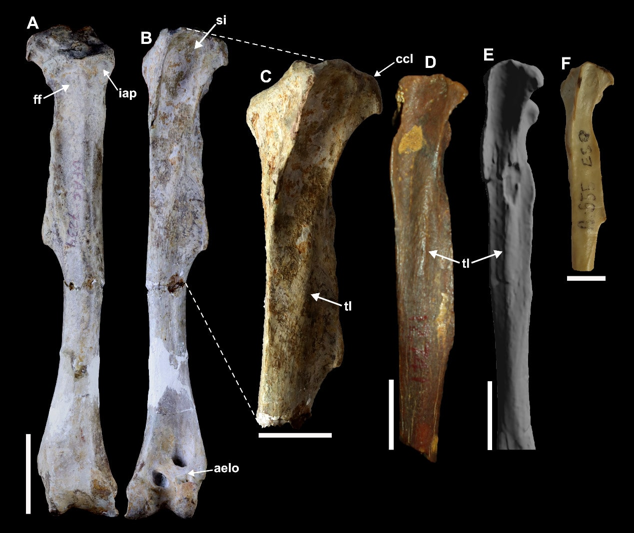

The bird is known from several vertebrae, femurs, and pelvic bones. In a study published in the journal Palaeoworld, Brazilian paleontologists examined the structure of a new tibiotarsus—the bone between the femur and tarsometatarsus from the left leg of Ma.ranzii. They compared the morphology of the find with other extinct anhinga species and reassessed the average body weight of this feathered giant.

A complete tibiotarsus was discovered near the Brazilian city of Boca do Acre, and its size was comparable to previously found pelvic bones of Ma.ranzii from the same location. Paleontologists even suspected that they belonged to the same individual. After identifying the discovered bone, the authors of the article estimated the probable body weight of all fossil anhingas using two different methods.

The lightest was Anhinga minuta—scientists calculated its weight at 790 grams. The same method indicated that the studied Ma.ranzii averaged 14.39 kilograms. However, using a different calculation method, the maximum average weight of this bird reached 19 kilograms, nearly a quarter higher than the initial result. The next largest was Ma.paranensis with a calculated weight of 8.32-9.97 kilograms. Paleontologists expressed skepticism about such sizes for the ancient water bird, as there are some proportional differences between the genera Anhinga and Macranhinga.

Nonetheless, a 19-kilogram bird is quite realistic today—just look at the well-fed African kori bustard (Ardeotis kori), which can sometimes grow to the same weight of 19 kilograms. For that to happen, however, a favorable environment, abundant food, and other conditions are necessary.

As researchers suggested, the expansive wetlands in the western part of the Amazon during the mid-Miocene, around 10 million years ago, could have allowed Ma.ranzii to reach such sizes, as the bird's diet consisted of large fish.