Lunar soil brought back by the Apollo missions contained traces of Earth water.

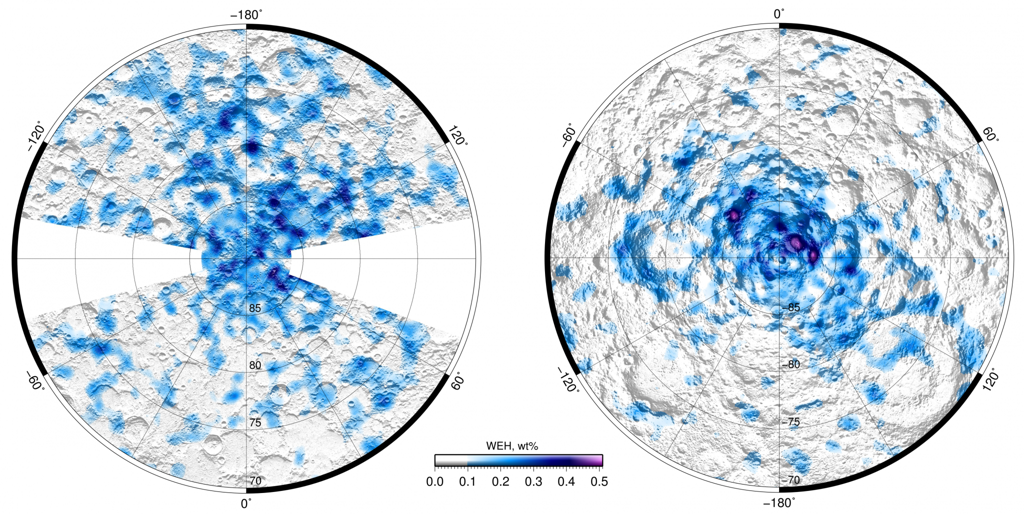

Water in lunar soil was actually discovered right after its delivery to Earth by both American astronauts and Soviet spacecrafts like Luna-16, Luna-20, and Luna-24. At that time, it was met with skepticism: the findings were believed to be a result of terrestrial contamination. Many years later, substantial water reserves on the Moon were confirmed by various satellite instruments. It’s worth mentioning the Russian detector "LEND" aboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which allowed for the creation of a comprehensive map of lunar ice deposits. This discovery sparked interest among space-faring nations to establish permanent bases in the lunar permafrost near the South Pole.

In the eternal darkness at the bottoms of lunar polar craters, water exists as separate ice particles, but even on the surface, in well-lit areas, water molecules can be found. However, they are not present "on their own," but are "embedded" within the crystalline structure of minerals in the soil. This phenomenon is known as rock hydration. The lunar samples brought back to Earth were found to be hydrated—though not as much as terrestrial samples, the Moon turned out to be not completely devoid of water.

Interestingly, after obtaining all these soil samples (a total of hundreds of kilograms), researchers intentionally chose not to analyze all of it at once; instead, they "preserved" most of it for future analysis, waiting for more advanced research techniques to become available. Therefore, to this day, these samples continue to be retrieved from storage and analyzed in minute quantities, yet even a few grams can lead to significant discoveries.

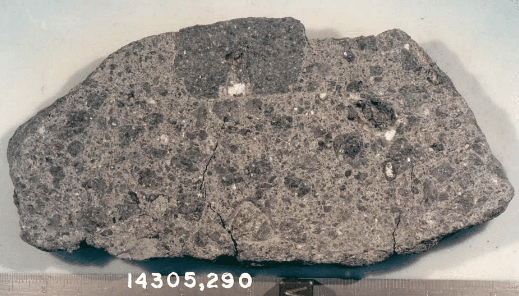

Recently, planetary scientists from the University of California, San Diego (USA) and the University of Edinburgh (UK) utilized nine different samples collected during the Apollo program, specifically from the Apollo 11, Apollo 12, Apollo 14, and Apollo 17 missions. Thus, the soil was gathered from the Sea of Tranquility, Ocean of Storms, Fra Mauro crater near the Sea of Serenity, and the Taurus-Littrow valley at the edge of the Sea of Clarity, respectively.

The researchers aimed to extract water from the minerals in all these soil samples and examine what it consisted of. They extracted it by heating the samples first to 50 degrees Celsius, then to 150 degrees, and finally to 1000 degrees Celsius. It turned out that some water was released even at low temperatures, while certain molecules could only be "detached" at 1000 degrees. This indicates that one portion of lunar water is loosely bound to the minerals, while another is very tightly integrated.

All the lunar water molecules extracted in this manner were compared to H2O found in terrestrial rocks and various meteorites of the most common type—chondrites, which are stones with numerous "chondrules": grains and inclusions. The comparison was based on the types of oxygen atoms present in the water molecules. There are three stable isotopes: oxygen-16, oxygen-17, and oxygen-18. It’s important to note that these numbers represent different quantities of neutrons in their atomic nuclei. Almost all oxygen in terrestrial water is oxygen-16, and there are only trace amounts of the other two isotopes. In extraterrestrial rocks, the situation is somewhat different, with varying ratios of these isotopes in different substances.

The results of their comparative study were shared by the scientists in an article for the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They wrote that the majority of the lunar water studied, based on the oxygen "signature," was most similar to water found in enstatitic chondrites—very rare meteorites that resemble terrestrial material. The oxygen in these meteorites is indeed similar to that on Earth. There is a hypothesis that these rocks contributed significantly to the formation of Earth and "brought" a large portion of its water during the early history of the Solar System.

Thus, according to the scientists, the discovery of the similarity between lunar soil and these meteorites signifies two things: that lunar water is largely terrestrial water and that Earth indeed received it from enstatitic chondrites.

Planetary scientists also noted that they found a considerable amount of cometary water in the Apollo samples; however, they discovered less of another type of water than expected: this refers to water formed under the influence of solar radiation. Specifically, protons continuously travel from the Sun, and each one needs just a single electron to become a complete hydrogen atom, which happens successfully on the lunar surface. This hydrogen then interacts with the abundant oxygen atoms found in lunar soil, resulting in H2O.

Until now, many researchers believed this to be the primary source of lunar water. The problem is that if this were the case, the oxygen in the molecules of this water should be identical to all the other oxygen in lunar soil. The current study has shown that, for the most part, it is different.

Planetary scientists emphasized that they did not expect to find so much terrestrial water on the Moon: according to the widely accepted theory, Earth acquired its natural satellite from debris resulting from a catastrophic collision with a Mars-sized planet. It was assumed that all the water from the ejected material would have quickly evaporated. Now it appears that this is not entirely true.

Naked Science previously reported on an alternative theory of the Moon's formation—the multi-impact hypothesis. Within this framework, most of the lunar material consists of debris ejected from Earth by asteroids. Since the energy from asteroid impacts is vastly lower than that from planetary collisions, such debris did not melt and could have delivered terrestrial water to the Moon.