Where in the body do people feel emotions? Researchers compared modern individuals to those from Mesopotamia.

The human body and brain have a complex relationship, and when it comes to emotions, things become even more intricate. Researchers clearly understand that emotions have a direct impact on the body, many of which can be physically felt. Grief is perceived as a "broken heart," love as "butterflies in the stomach," anger as tension in the jaw, and stress as an "iron band" around the chest and head.

However, these are modern interpretations. Have people always felt—or at least expressed and described—emotions in the same way? An interdisciplinary group of researchers discovered that the perceptions of where emotions "live" among the inhabitants of Mesopotamia and modern individuals can vary significantly.

The scientists analyzed texts from the Neo-Assyrian Empire to understand how people experienced emotions in their bodies. The data set included a million words in ancient Akkadian, inscribed on clay cuneiform tablets created between 934 and 612 BC. Modern body maps of emotional sensations were compiled ten years ago by researchers under the leadership of Lauri Nummenmaa (Lauri Nummenmaa). The findings of the study were described in the journal iScience.

In ancient Mesopotamia, people already possessed basic knowledge of anatomy and recognized the importance of the heart, liver, and lungs. These organs, along with the hips and mouth area, were frequently mentioned as the most common places where emotions were felt.

Maps of bodily sensations related to happiness for modern individuals and Mesopotamians largely overlap, except that the ancient inhabitants placed greater emphasis on the liver. Happiness in their texts was described using words like "open," "radiant," or "full."

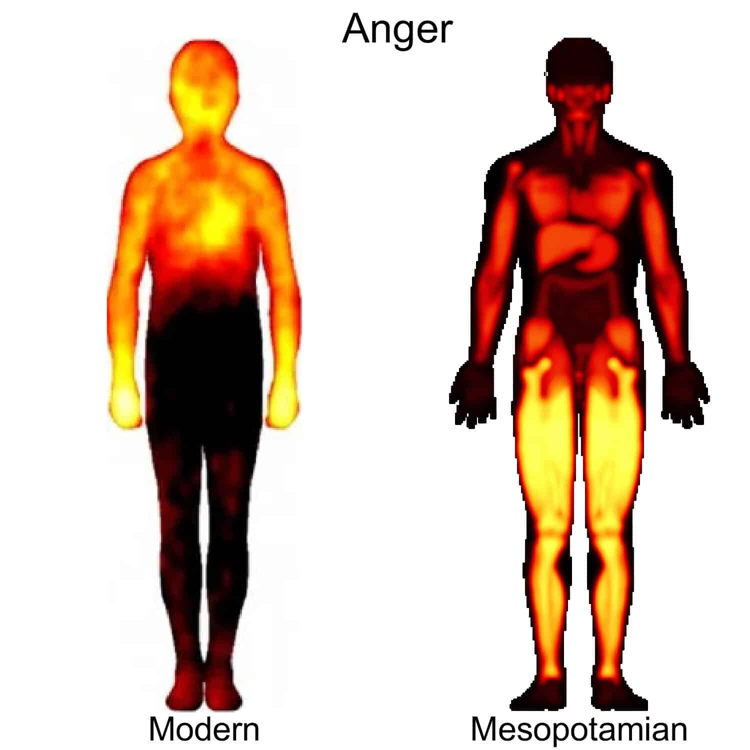

The differences between us and the ancients are particularly noticeable in the sensations of anger and love. Modern individuals experience anger in the upper body and arms, while for Mesopotamians, it was expressed through "heat," "fury," or "irritation" in the legs.

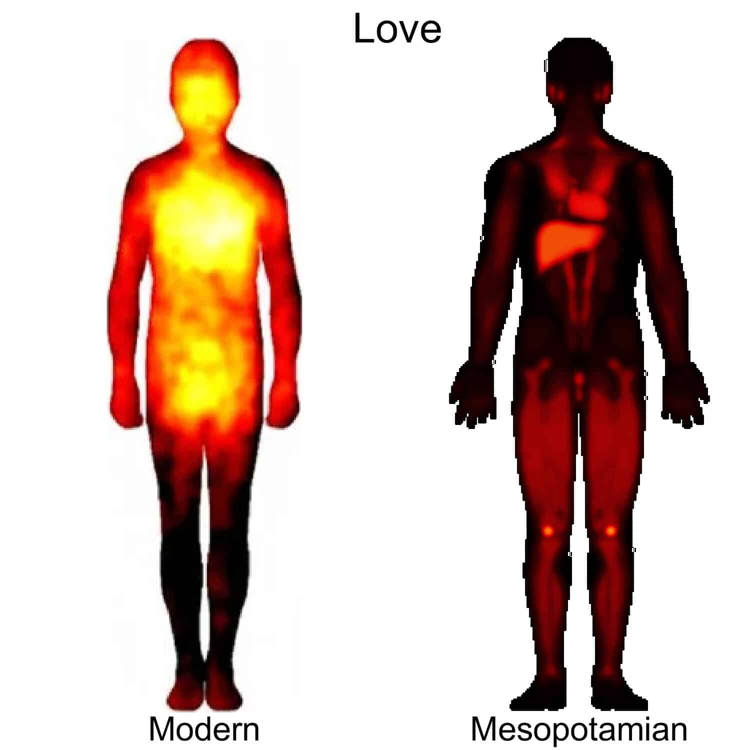

Love, however, is felt similarly by us: it is centered in the chest area. In Mesopotamia, love was especially associated with the liver, heart, and knees, while in modern individuals, sensations shift toward the head and genitals.

It is important to note that cuneiform was primarily created by scribes at the request of wealthy individuals, so the texts do not provide a complete picture of emotional perception for all Mesopotamians. Nevertheless, the cuneiform clay tablets contain a variety of texts: tax lists, purchase and sale documents, prayers, literary works, as well as historical and mathematical records. Together, they offer a sufficiently broad descriptive foundation.

“It remains to be seen whether we can speak of typical emotional experiences for all humanity and whether, for example, fear was always felt in the same parts of the body. It is also essential to remember that texts are just texts, while emotions are experiences lived in the moment,” emphasized Professor Saana Svärd (Saana Svärd) from the University of Helsinki in Finland, an Assyriologist and project leader.

The researchers noted that while comparing such data is intriguing, it is necessary to consider the differences between modern body maps based on self-reports and the body maps of ancient Mesopotamians, which were constructed solely from linguistic descriptions.