Vasiliy Klyucharev: "You can believe in free will, but that doesn't mean it truly exists."

— What do you think, do we have free will and what does it even mean? Can it be considered a manifestation of not only conscious but also unconscious motives? After all, theoretically, we can be held responsible for what enters our consciousness — it's a motive to better understand ourselves and develop "awareness".

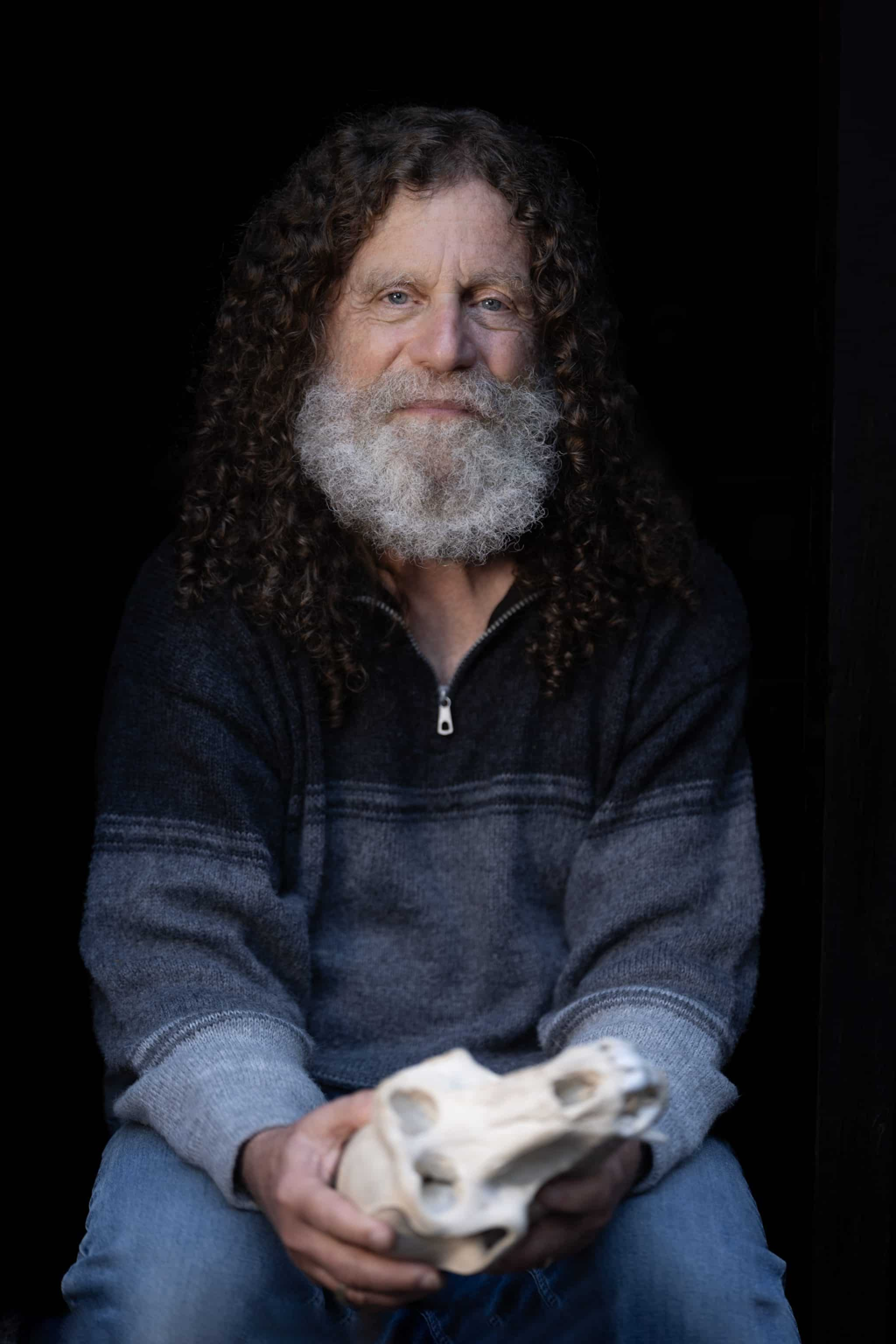

— I sympathize with the ideas of the well-known neuroendocrinologist and primatologist Robert Sapolsky, who argues that free will does not exist. Regarding the definition, in this case, the opinions of not only neurobiologists but also philosophers are important. They have been struggling for centuries with defining the term free will and still have not found a clear answer. One could use the definition of free will as "the ability to follow one's desires" even when we are guided by certain unconscious motives. But here's a vivid example — a pathological maniac, clearly driven by both his conscious and unconscious motives. He clearly acts as he wishes. But is he completely free in his actions?

There will be those who say: yes, he is free, a person is free to choose how to act. Others will argue the opposite. However, if we look at this from the perspective of cause and effect, there is always a reason for a certain action or thought. Specific genetics, childhood traumas, social conditions, a history of experiencing violence, a pathological hormonal background, or brain dysfunction — all can lead to deviant behavior. Does this person have free choice, or is he predictably "determined" to become a manic criminal?

Let's take a simpler example. If we rewind the history of the construction of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, we will see: its tilt is a consequence of an engineering error. For the tower not to lean, that error should not have existed in the first place. No matter how many times we build a tower based on a flawed design using unsuitable materials, the result will always be the same — it will fall. Mentally rewind time for anyone at the moment of their decision-making. The decision had certain causes (mood, available information, hormone release, anything) and it was precisely because of them that it was made. For another decision, other causes are needed, just as a different plan and different materials are required for the tower not to fall.

Therefore, such a thought experiment with rewound time allows us to realize that the decision made cannot be any different. It is an illusion that we could have made another decision; either we or the circumstances would have to be different for that to happen. Thus, we can break down the causes of any phenomena — including our thoughts and actions. We simply do not always see these causes; often, we have no idea about certain regularities that we either call randomness or a decision made by our intuition. In reality, a multitude of hidden and obvious causes lead to a specific outcome, and they could not lead to any other.

But there are random processes in physics and chemistry, right?! According to quantum physics, there are. But they cannot influence a one-and-a-half-kilogram brain. Even if they could, a random decision is not a free one; it definitely does not depend on us. The mechanisms of our decisions are governed by strict laws of nature, even if some of them remain unknown to us. We ourselves are products of nature; the laws of physics and chemistry also act on us and our brains. Certain physicochemical reactions occur in our brains, always following specific algorithms. For our decision to be different at a certain moment in time, other processes in our brain would have had to occur. There would have to be different conditions: a different immediate moment, a different environment, a different state of health, a different history of development, different genetics, finally. From this arise the inevitable questions — is a person responsible for his crime or not? Should we admire the achievements of some artist or professor? Or could they not have been otherwise?

— Can we choose which of these physicochemical reactions to initiate?

— Today, with the help of complex equipment, we can observe at what moment the brain makes a decision based on its activity. Suppose we can tell ourselves — I will not make a decision. In his time, Libet himself showed that there is a certain time window when a person can cancel his decision — not to make it. He was convinced that this is the moment of freedom — the ability to reverse the initiated process. But in reality, if we talk about cause and effect, the question arises again — what made you decide to cancel your decision?

This new decision fell from the sky; can you claim it had no causes? No, you cannot. And you begin to unravel another causal chain. Perhaps related to more complexly organized areas of the brain, which initially planned something and then decided to prove to themselves that they are free. But there, a causal thread was initiated, predicting that you would reverse your previous plan. That is, certain neurons were determined to make the decision "not to make a decision." Do you understand? And even if we assume that some random processes are possible, what does that have to do with your freedom? After all, it wasn't you who made the decision — it was just a coincidence.

— If we assume that our decisions are determined by our unconscious, can we work with it in a way that doesn't change it but at least allows us to understand in advance where we are being "led"?

— I will express my opinion. Of course, in principle, I can go to a psychoanalyst or a behavioral psychotherapist, who will start working with me, unfolding my childhood memories or developing new reactions to certain situations. Or, for example, I could make an appointment with a psychiatrist — he would prescribe me medication for a psychiatric disorder. But again, we face the same question — what made us decide to consult a specialist; was that decision free? In the sense: could we have not made it?

— How should we deal with criminals in this case?

— Interesting ideas on this are expressed by the well-known scientist Steven Pinker. Imagine this: a lawyer stands in court and shows an MRI scan of his client’s brain with something like this: "Look, he couldn't help but kill. His amygdala, associated with the fear of punishment, is five times smaller than that of a normal person; he doesn't learn from his mistakes, and his parents couldn't teach him anything." In a normal situation, he would be sent for treatment with the formulation that the person is not responsible for his actions. But a "new formation" judge, doubting the existence of willpower, does not send him to the hospital but says: "Since his amygdala is reduced five times, and he learns from his mistakes five times worse than an ordinary person, then his punishment should also be proportionally increased — by five times. He will not go for treatment but to prison and will be punished five times more severely." By the way, there are already cases in global legal practice where the lawyer's data about the client's brain influenced the judge's decision.

There is a famous example described in scientific literature when one of the social workers suddenly began to show a tendency towards pedophilia. They scanned his brain, and there was a gigantic tumor in the emotional regulation center. They removed it. And what happened — the pedophilia immediately disappeared. And then, when the tumor returned, the symptoms emerged again. This episode sparked a large-scale discussion about a person's responsibility for his behavior. This is a striking case where a specific brain inevitably forms certain behavior.

Therefore, when we accept the concept of the absence of free will, we begin to relate to a person differently — more mechanistically, breaking down his behavior into components. That is, the awareness of the absence of personal responsibility for actions (after all, a criminal or simply a bad person could not have behaved otherwise) does not mean that we cannot change the behavior of those dangerous to society and have no opportunity to control it. Sapolsky, for example, gives the example of ships that once arrived from long voyages. They were quarantined for several months, understanding that they could bring, for example, the plague. No one blamed those sailors, but they were isolated from society. In a similar way, Sapolsky suggests we treat criminals: not punishment but quarantine. We do not blame the person — he is who he is, but we have the right to send him to quarantine.

— Due to the awareness of the absence of free will, a person may develop certain fatalistic moods, melancholy, and depression, as happens with Sapolsky himself. What do you think should be done about this?

— I became fascinated by the topic of free will about 20 years ago. Once, I worked in the Netherlands, where it is customary to drink coffee with colleagues during the day. And at one of these gatherings, I asked them, since you have a Protestant society, and for Protestants, everything is predetermined by divine providence: who is bad, who is good, what will happen to you. Why are you so active: traveling, earning, building? My colleagues replied something like this: if everything is determined by God, then we are just trying to notice His decision within ourselves, so for us, it is a great joy to discover that we are chosen active, good Christians. If we are bad, it means we will end up in hell, so there is a reason to