Byzantium and Russia: How Did We Become Heirs of the Eastern Roman Empire? An Interview with Sergey Prokopenko.

[Naked Science]: How did the connections between Rus and Byzantium begin?

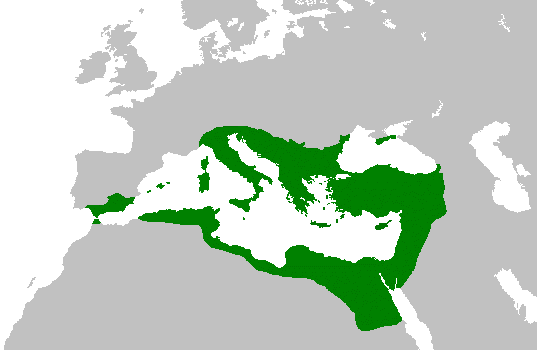

[Sergey Prokopenko]: By the time the Slavs were finally recognized as an ethnic group, Byzantium was the dominant state, much like the USA in the late 1990s. Byzantine authors such as Procopius of Caesarea and Maurice referred to the Slavs as Antae or Sclaveni. They regarded the Slavs as barbarians, which is understandable—our ancestors lacked statehood and writing at that time. They practiced paganism and behaved quite aggressively, regularly raiding Byzantine territories. In the 7th and 8th centuries, they even settled within the Byzantine Empire, reaching the Peloponnese. Roman emperors periodically relocated Slavic tribes from the Balkans to Asia Minor to combat the Persians and Arabs, but this migration policy failed: the settlers often sided with the enemy, and the number of Slavs in the Balkans was so great that in Thessalonica, the birthplace of Saints Constantine and Methodius, everyone spoke both Greek and Slavic from childhood.

It is not surprising that Byzantine authors described the Slavs in unflattering terms. At the same time, Byzantium continued its policy of treaties with federates—allies of the Roman Empire who lived along its borders and protected the territories. The Byzantines were diplomats—they preferred to negotiate with some while engaging in warfare with others. Thus, the cunning and calculative nature of the Byzantines indeed became notorious.

[NS]: What happened next?

[SP]: In 860, the confederation of tribes known as "Rus" entered the political arena, with warriors daringly attacking Constantinople. Two years later, Prince Rurik and his retinue arrived in Ladoga. This period saw the vigorous growth of the Rurik settlement, and later, the founding of Great Novgorod. However, from the 7th to the 9th centuries, Byzantium faced a serious onslaught from the Arabs, cutting off trade routes, and Constantinople was then a highly developed trading hub where one could buy or sell anything.

It was then that the famous route from the Varangians to the Greeks began to take shape, around which our state started to form. Trade also developed along the second route—from the Varangians to the Khazars. Clearly, as statehood emerged, Rus began to actively integrate into trade relations with Constantinople. From then on, they not only waged war but also traded.

Even then, Christianity was actively penetrating the consciousness of the Slavs—long before the baptism of Rus. Recall the baptism of Princess Olga—before Vladimir baptized Rus, the groundwork had already been laid. Finally, during Vladimir Sviatoslavich's pagan reform, two Varangian Christians were martyred for their faith, indicating the existence of a Christian community in Kiev prior to 988.

[NS]: Byzantium was a center of culture and technological progress. What did the Slavs adopt from it?

[SP]: Given the immense influence, we certainly could not help but adopt Byzantine achievements. However, mere copying of results will never lead to success—there needs to be a personal reinterpretation. A powerful surge in cultural development occurred—both material and spiritual.

Thanks to interactions with Byzantium, Rus rapidly progressed through several stages of development. As a result, our ancestors quickly mastered the basics of literature and art that Byzantium transmitted. It is important to remember that the Eastern Roman Empire, unlike the European version of development that inherited the traditions of the Western Roman Empire, had no break from Antiquity.

After the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Europe seemed to reformat and recreate itself. However, Byzantium continued its development without such a rupture. This experience was passed down to us.

[NS]: What specific examples or monuments illustrate this?

[SP]: Stone architecture came to us from Byzantium. For example, the Church of the Tithes in Kiev (which has not survived). It was built by Byzantine masters, while Russian craftsmen were involved in constructing the cathedrals of Saint Sophia in Kiev, Novgorod, and Polotsk. There was nothing shameful about copying in Rus. We know this because the masonry of the same Cathedral of St. Sophia in Kiev alternates layers of plinthos—wide baked bricks used by the Byzantines to enhance seismic stability.

For the Russian plain, this was not initially relevant, but at first, the cathedrals in Rus were indeed built using plinthos. Later, this practice became established in Russian architecture and persisted until the 15th century.

In addition to stone architecture, frescoes, mosaics, and icon painting also came to us from Byzantium. All miraculous Russian images, according to tradition, trace back to the times of Constantine and Vladimir Monomakh, that is, to the 11th-12th centuries, as do state symbols—the Monomakh's Cap, the robes, and the scepter with the orb. Byzantium had secular mosaics and frescoes, but fewer have survived compared to ancient Russian ones.

Many crafts also came to us from Constantinople. For example, glassblowing, plinthos production, jewelry techniques for working with silver and gold (filigree, granulation, blackening, gilding, etc.), gold embroidery, and silk and satin embroidery.

[NS]: During the Soviet era, little was said about Byzantium and its connections, so we know very little. What facts about it have become the domain of historians? What myths do we still believe?

[SP]: Indeed, this is a problem. In the realm of historical science, Byzantium is a state whose memory has been neglected and not seriously studied. In the West, if it was studied at all, it was often done from a condescending perspective. As a result, many myths (and they are international) about Byzantium have emerged from the work of Western scholars.

The first of these is the very term "Byzantium." It was introduced into scientific circulation by the German historian Hieronymus Wolf in 1557. He used the word "Byzantium" to refer to the Eastern Roman Empire in his work "Corpus of Byzantine History." This term derives from the name of the ancient Greek colony—Byzantium, founded by Dorian colonists from Megara in the 7th century BC at the site of future Constantinople. Thus, historians seemingly marked the rupture between Byzantium and the Roman Empire, denying continuity.

The term became established and then circulated from work to work. In reality, it is more correct to call Byzantium the Eastern Roman Empire or simply the Roman Empire. The Byzantines referred to themselves as Romans (Romeis). Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire abandoned Latin as its official language in the 7th century and switched to Greek—the main language for the majority of the population of the state.

This gave rise to another myth, that Byzantium was exclusively an eastern center with no relation to European civilization. In reality, it is the same Europe—a civilization that arose on the foundations of Roman statehood, Christianity, and Greek culture.

Byzantium is not less but more of a bearer of European values, because—as I mentioned above—its history had no break from Antiquity.

Another myth is that the history of Byzantium is a story of slow decline and degradation. This is untrue. The Eastern Roman Empire was a period of flourishing architecture and art. Culture was at a very high level. From a large number of sources, it is known that the average literacy rate in Constantinople was around 60-70 percent. This means that more than half of the people could read and write. In those times, that was a significant figure.

At the same time, in the rest of Europe, these figures were several times lower. There are examples of discoveries by Byzantine scholars that are little known but were ahead of their time. For instance, the philosopher and astronomer Nicephorus Gregoras calculated the inaccuracies of the Julian calendar as early as 1326. He proposed a reform to the Byzantine emperor, but it was rejected. However, in the 16th century, at the behest of Pope Gregory XIII, these calculations were used to create the Gregorian calendar in Europe.

Another myth: Byzantium was a deep Middle Ages with strict patriarchy, strong monarchical power, almost a totalitarian state. In reality, things were somewhat different. Already in the Justinian Code in the 6th century, it was established that all are equal before the law—even the emperor. For that time, this was very progressive.

Women in Byzantium also enjoyed certain freedoms. Compared to medieval West, this was like a cosmos! Wealthy and aristocratic women not only entered the elite but also participated in major and fateful decisions for the country. Comparing Constantinople and Paris in the 12th-13th centuries is like likening modern Moscow to a small provincial Russian town.

[NS]: How did Byzantium lose its power?

[SP]: