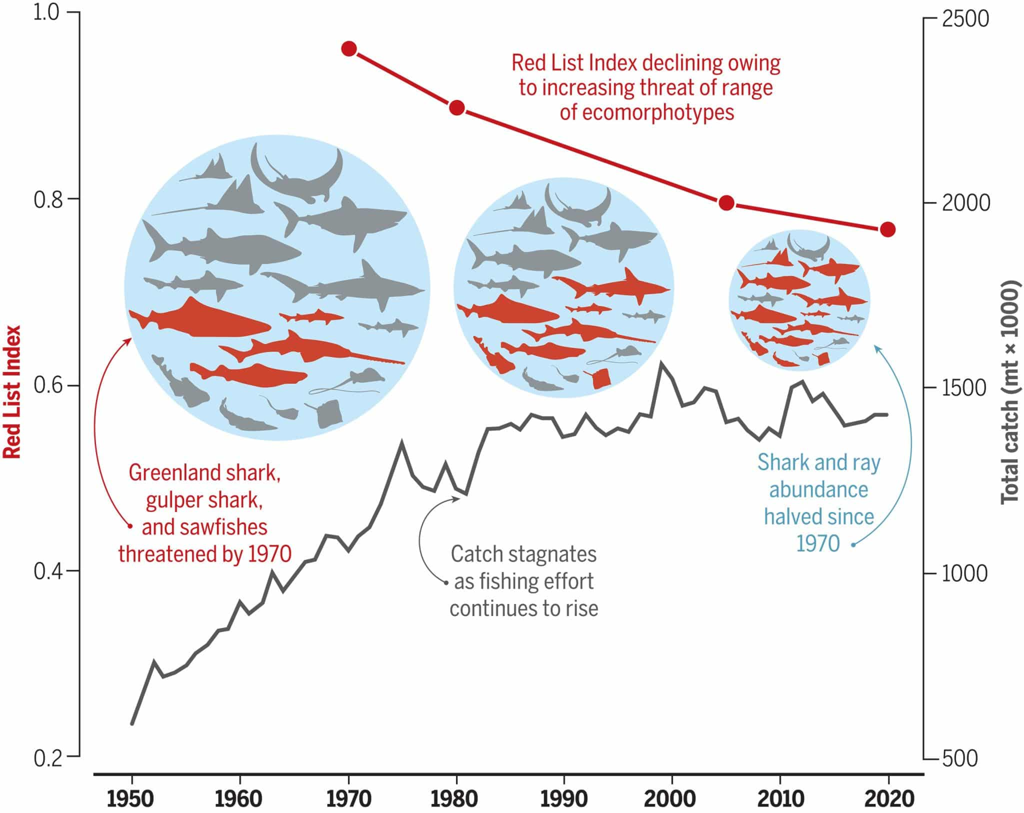

In the past fifty years, shark and ray populations have declined by 50%.

Fish are a vast group of primary aquatic vertebrates characterized by a diverse composition. Alongside ray-finned fishes, which comprise the overwhelming majority, other, more ancient species, including cartilaginous fish, inhabit the seas.

There are not many representatives of this class, with only about 1,200 species of sharks, rays, and chimeras (whole-headed). Almost all of them are predators at a high trophic level, which has earned them a reputation for being dangerous and well-protected. However, in reality, they are quite vulnerable and are far more often victims of humans (including as food) than the other way around.

A new article published in the leading scientific journal Science evaluates the dynamics of cartilaginous fish populations over the past 50 years. Starting in the 1970s, their catch increased rapidly, peaking in the 1980s. However, after that, the volume of caught fish began to decline, despite doubled efforts by fishermen.

The authors note that the self-reproductive potential of sharks and rays may have been undermined at that time. To assess the scale of the problem and identify the causes, researchers obtained an RLI for cartilaginous fish—an index based on the IUCN Red List (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Such calculations are actively used for the conservation of terrestrial ecosystems, but have not yet been applied to the World Ocean.

The calculations cover various natural habitats from the 1970s to the present day. They vary by geographical location, water depth, and ecosystem diversity. This allowed biologists to map the "bright spots" of cartilaginous biodiversity (where RLI changed little and fish overall are doing well) and "dark spots" (where the diversity of sharks and rays sharply declines).

The authors considered that these fish represent different ecomorphotypes: they differ in structure, size, and lifestyle. Scientists determined which ecological groups of cartilaginous fish have suffered the most and what the reasons are, including the contributions of various regions of the Earth and individual countries to the problem.

According to estimates, in addition to the average loss of half the populations, globally, rays and sharks have lost 19 percent of the RLI index. Initially, the trend affected rivers, estuaries, and other coastal waters, and later spread to the open ocean and its depths.

The loss of ecomorphotypes, which describes the lost functions of fish in communities and is referred to as "ecological erosion," amounted to 22 percent. According to the authors, the main culprits are countries with weak economies, low fishing efficiency, and large populations in coastal areas.