Darkening the Earth's sky could save 400,000 lives annually.

In 1971, Soviet climatologist Mikhail Budyko proclaimed the inevitability of global warming due to anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions. At that time, his idea was met with skepticism from nearly all other scientists, but since the 1980s, the increase in global temperatures predicted by Budyko has become a reality. The forecasted rise of 1.0 degrees by 2020 also occurred on schedule.

While Budyko viewed the global warming he predicted as a benefit that would enhance the habitability of Earth, contemporary climatologists have deemed climate change as a negative phenomenon, despite the fact that this change resulted in a record increase in terrestrial biomass. Consequently, there have been calls to combat warming. The approach chosen in the West (solar and wind energy), as Naked Science has already noted, will not be able to halt the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere. Therefore, many Western scientists have advocated for global dimming—spraying sulfur aerosols in the stratosphere (“Budyko's blanket”).

Sulfur dioxide will reflect solar energy back into space, creating an anti-greenhouse effect. Such phenomena have occurred after major volcanic eruptions in the past— for instance, the mass starvation deaths during the Time of Troubles or the legends of Fimbulwinter and Ragnarok emerged following such eruptions in the 17th and 6th centuries, respectively. Some researchers acknowledged the effectiveness of global dimming in combating warming but expressed concerns that it could lead to reduced crop yields or moderate acid rain.

The authors of a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences set out to determine the costs of global dimming and compare them with the benefits. To do this, they employed computer modeling to analyze the change in mortality rates with a reduction in global average temperature by one degree.

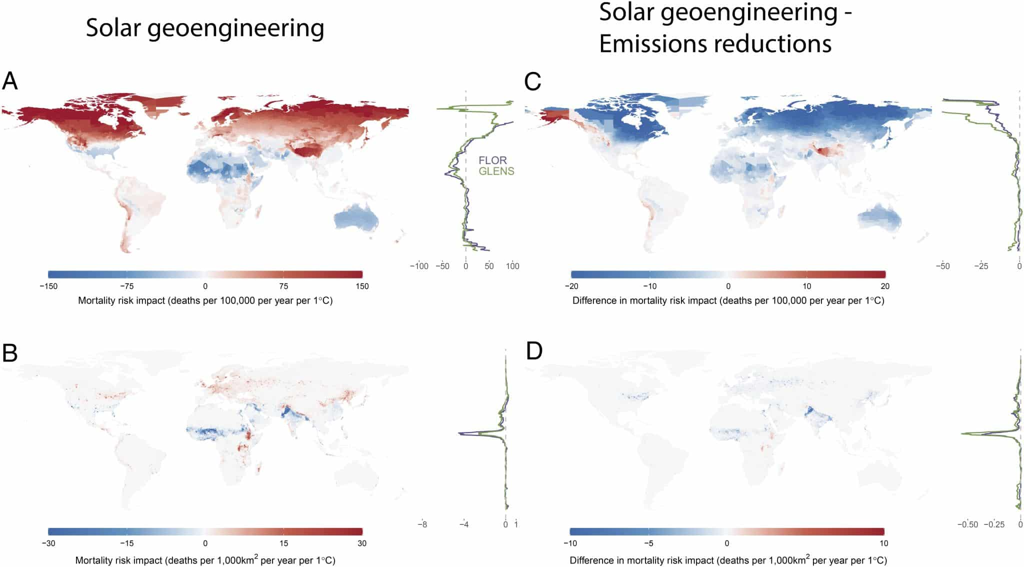

According to their calculations, this would result in a decrease of 400,000 deaths per year due to non-optimal temperatures on Earth. Meanwhile, the estimated number of deaths attributable to the global dimming project would amount to only tens of thousands—13 times fewer than the number of lives saved each year. Interestingly, global dimming, according to the scientific study, would save more lives than combating warming through the reduction of CO2 emissions. This seemingly strange conclusion arises from the fact that the fight against CO2 would reduce temperatures more significantly in colder regions of the planet, while global dimming would have a greater effect in tropical and equatorial areas.

The new research has certain limitations. Its authors—climatologists—assumed that “equatorial regions generally benefit from cooling, as the reduction in heat-related mortality outweighs the increase in cold-related mortality.” In reality, doctors have long established the opposite: cold-related mortality is highest in Africa—1.19 million compared to 0.026 million deaths from heat. Globally, the ratio is quite different: 4.59 million deaths from cold versus 0.49 million deaths from heat. This means that in hot countries, people are more likely to die from cold than from heat. This occurs because the human body adapts well to heat, but can only cope with cold through heating and warm clothing, which are in short supply in Africa.

Moreover, the authors of the study estimated that a one-degree cooling would reduce global mortality by 400,000 per year based solely on computer models. Meanwhile, global warming of one degree has already occurred (from 1970 to 2020), yet there was no increase in temperature-related mortality during this period.

On the contrary, as noted by doctors, such mortality fell by 166,000 people per year in just the first 16 years of the 21st century. This happened because cold-related mortality is significantly higher than heat-related mortality, which is why warming has decreased the overall frequency of temperature-related deaths. If the already realized warming of one degree could lead to a reduction in deaths from non-optimal temperatures, it is quite difficult to understand how future cooling by the same degree would not result in an increase in temperature-related mortality.