The teeth of early Homo evolved more rapidly than their brain.

The oldest remains of the genus Homo discovered outside Africa were found in 1991 in Dmanisi (Georgia). Local scientists even attempted to classify these specimens as a separate species — Homo georgicus. However, nowadays, they are most often associated with Homo erectus or referred to as a transitional form from Homo habilis to erectus.

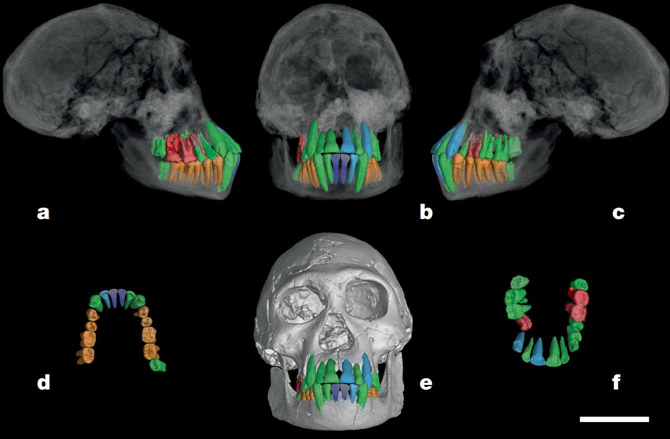

In addition to various bone remains, five fairly complete skulls with lower jaws and well-preserved teeth have been found in Dmanisi to date. Three of these belonged to adult individuals who were not very old, while another belonged to a rather elderly Homo.

Only one tooth remained in his jaw, while the sockets of the others had closed up with bone tissue. Without advanced cooking technologies (such as meat grinding or fire boiling), survival for such an individual would have been challenging. It is likely that he was cared for by his fellow tribesmen, indicating a relatively high level of community development.

The fifth skull belonged to a person who died around the age of 11. Christoph Zollikofer (Christoph Zollikofer) from the University of Zurich (Switzerland) and his colleagues analyzed the microstructures of the teeth of this ancient Homo using synchrotron phase-contrast tomography. The results of their work were published in the journal Nature.

At the time of death, the adolescent's teeth were nearly fully formed. The authors of the new study suggest that the age of so-called dental maturity for this hominin was 12-13 years. This significantly differs from the age at which modern humans achieve complete tooth formation (which occurs between 18-22 years).

By around 12-13 years, the growth of teeth in modern apes also concludes. Researchers compared these findings with what is known about tooth growth in australopithecines. Recall that these extinct higher primates practiced bipedalism, likely used stone tools, and exhibited anthropoid features in their skull structure.

The front teeth of the adolescent from Dmanisi also grew similarly to those of apes. However, the molars developed significantly more slowly, resembling the pattern seen in Homo sapiens. Essentially, the dental system of the Dmanisi hominin matured slowly during the early years of life, with a sharp increase in tooth growth occurring right around the age of five. In modern humans, this growth spurt happens closer to the age of seven.

Researchers noted that the differences in tooth development between apes and humans may be explained by the fact that humans wean their children off breastfeeding much earlier and transition them to solid food. Consequently, the age of dietary independence from adults comes later. Female apes nurse their young for a much longer period, and by the end of weaning, the offspring are usually capable of foraging for food independently at an earlier age than humans.

The scientists questioned why humans extend the period of dietary dependence of children on adults compared to ape-like beings. Modern science suggests that between the ages of two and four, the overall physical development of a Homo sapiens child slows down: both body and tooth growth are reduced.

This is typically explained by the notion that during this period, the body directs all its energy towards brain growth, which is significantly larger in humans than in other higher primates. In other words, what distinguishes us from apes is a relatively prolonged childhood during which the child develops and remains dependent on adults.

However, this explanation does not hold in the case of the early human community from Dmanisi. The brains of these Homo were only slightly larger than those of modern chimpanzees.

Homo erectus, to which these hominins likely belong, significantly increased their brain size over the course of evolution, but this happened much later. Around 1.85-1.77 million years ago (the dating of erectus remains in Dmanisi), their brains were still too small to require a large amount of energy for growth.

The authors of the study proposed that the use of stone tools for softening food reduced the evolutionary pressure that would compel teeth to develop quickly in the early years of life. They emphasized that not all changes in human development are due to increases in brain volume. Sometimes, life circumstances (biological or cultural) can be more significant.